Those who suffered the most were those who were taken on by the “support department” of the call center, whose task was to extort maximum money from customers by any means, not shunning rude psychological pressure. Some were pressured into taking out huge loans or threatened using letters purporting to be from British financial regulators demanding they pay taxes. Sometimes fake lawyers got in touch and offered to return the money – also not for free. In the most egregious cases, Milton Group “support” forced clients to install programs on personal computers and then could remotely control them and steal money. Some ended up losing over $200,000.

Blinded by promises of sky-high profits and resounding foreign names and addresses, the victims of the scams believed they were dealing with a solid investment company in Western Europe. Little did they know that on the other end of the phone line were mostly young Ukrainians or migrants from Africa and the Middle East who had settled in Kyiv.

Some deceived people reported the stolen money to the police of their countries, but law enforcement officers, as a rule, could not get the whole picture of what happened. Cybercrime departments in numerous countries where the Kiev call center has its legacy, including Spain and Italy, have told OCCRP and the Center’s partners that they are aware of this cross-border scam. However, according to them, victims often do not report deception, and the whole scheme is difficult to trace, since interaction between law enforcement officers from many jurisdictions is required.

Attention! International phone scams

The massive scam by the Milton Group is an example of a scam involving the sale of fictitious financial products over the phone. A wave of such scams has swept the world in recent years – victims are lured with promises of quick profits through investments that have become popular: investing in binary options (betting on price changes up and down), playing on foreign exchange rates (in the market sometimes called Forex) and – more recently – buying cryptocurrencies, such as bitcoins.

Israel was the main “hub” for such fraudulent call centers until the country’s authorities in 2017 banned the giant binary options trading that flourished there. As a source in the Spanish police told the Madrid edition of El Confidencial, the scammers then began to relocate their schemes from Israel to other countries, such as Ukraine, Bulgaria, Albania, and Cyprus.

The same source said that the Spanish police were investigating several gangs that were likely operating fraudulent call centers, including one in Albania that “earned” ten million euros a week, more than half a billion euros a year. (Whether there is a link between the Albanian call center and Milton Group is unclear.)

The US authorities are tough on such fraud. Lee Elbaz, a former director of the Israeli firm Yukom Communications, was sentenced here last year. He was found guilty of running a $145 million binary options trading scam. The scammers acted in much the same way as the Milton Group. This is probably why, according to the corruption complainant, Milton employees were told not to target Americans as victims. They were also advised not to call residents of Israel, Ukraine and Belgium.

National cybercrime agencies told OCCRP and its partners that they are aware of the problem and are working closely with other law enforcement agencies to address it.

At the same time, many of the people interviewed by the Milton Group who were deceived by the Milton Group admitted that they either did not inform the local police about the theft of money from them, or realized that the police were not eager to investigate. According to Nunzia Ciardi, head of Italy’s Cybercrime Authority, many people still don’t report such incidents because they’re ashamed to admit they’ve been duped.

In turn, Alexander Fjelver, who is responsible for combating cybercrime at the largest Norwegian bank DNB, said that the country’s banks are trying to track fraud cases. At the same time, it is often difficult for them to convince customers that they are being deceived – the schemes of swindlers are so plausible and the psychological “processing” is so strong.

“You go to a certain page and see how much money you have invested, and a graph with changes in income. The graph shows that profits are growing and you want them to grow further, so you invest even more money,” says Fjelver.

“Anyone can be fooled. This is understandable: if you see an increase in your money and communicate with a person who is very skillful in persuading, then you believe in all this, ”he adds.

And yet now, based on a lot of evidence from the applicant about corruption, the Swedish authorities have launched an investigation and contacted Europol in connection with the findings.

“What this company does is all fiction,” said Aleksey, a corruption complainant (we don’t give his real name for his safety). “They just steal money from people.”

According to him, the staff was told that the Kiev call center in 2019 “sold” for a huge amount – 65 million euros. To celebrate the “success”, the company’s bosses threw a lavish New Year’s Eve themed party with a script based on the plot of the novel “The Great Gatsby” – about a bootlegger and a skilled schemer from the heyday of jazz. Under the neon lights, hundreds of Milton employees saw the numbers of torch dancers and gutta-percha acrobats. The most distinguished “salesmen” received generous bonuses, including money, cars and free rental housing.

Apparently, the Milton Group is connected to other call centers in Albania, Georgia and North Macedonia, where hundreds more people work.

In a number of situations, OCCRP has been unable to establish a link between the Milton Group and certain scams reported by the victims. This is not surprising given how many people have been repeatedly scammed by fictitious investment firms, who are, by definition, difficult to detect. However, many victims of the swindlers named well-known names of Kyiv call center operators and the “brands” they were selling.

While it is impossible to claim that all investment transactions through the Kiev call center were fraudulent, journalists from Dagens Nyheter and the OCCRP network were able to speak to more than 180 people on the list of “processed clients” from the Milton database. All of them confirmed that they lost money due to fraudulent schemes. Only a few managed to withdraw part of the funds – apparently, they were allowed to do this in order to push them to new investments. A few still hope that one day they will be able to pick up their “earned money”.

The “investment” required a transfer through Western Union, bank accounts, credit cards, or cryptocurrencies. Merchants at Milton received more commissions if they could convince customers to pay with bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies, since such transactions are more difficult to detect. Many interbank transfers were carried out through personal accounts of individuals in British financial companies. At the same time, there were clear instructions not to indicate that the money was going to investments.

In many cases, OCCRP found that online credit card payments were handled by a Cypriot company called Naspay, which offers, in its words, “a state-of-the-art payment service.” The company is owned by David Todua, a person with Georgian and Israeli citizenship, the same one whom the complainant about corruption called the owner of the Milton Group to law enforcement officers. (Todua himself vehemently denied having any “formal or informal” position within the company, although he admitted he was at the Milton Group’s New Year’s Eve party as a guest. According to him, Naspay does not process payments, but only “transmits information” between websites that accept payments and financial institutions (OCCRP found no evidence that Todua owns any stake in the company.)

After the initial investment, some clients were told by the scammers to send additional payments to individuals in countries as diverse as Colombia or Uganda rather than to the company’s bank account.

Leif Nixon, a Swedish cryptocurrency expert who helps law enforcement investigate bitcoin-related crimes, analyzed the addresses that the Milton Group used for customer payments in bitcoins. According to him, it does not look like they belonged to a legal operator.

Nixon cited several indications that client money was not being invested as promised. In particular, various people were repeatedly asked to send bitcoins to several identical addresses. Each client was given a different address for each of his transfers.

“It’s like you open a bank account but you don’t get an account number, and you get different numbers for different payments,” Nixon explained.

He claims that as a result, $5.9 million worth of bitcoins from seven Milton Group email addresses disappeared on East Asian cryptocurrency exchanges in 2019.

“I have no reason to believe that a legitimate business would make such transactions,” says Nixon. “They don’t make any sense.”

According to corruption whistleblower Aleksey, the staff at the Kiev call center knew the job was to steal money. As Aleksey told Dagens Nyheter, one of his first days at Milton, the sales manager laughingly said that even when she was six years old, she dreamed of “becoming a bitch and stealing people’s money.”

Last month, an undercover journalist participated in a training session for new staff at a Milton Group-affiliated Tbilisi call center. He heard the trainer say that the company’s goal is for customers to “lose their money realistically.” In response to the question “why?” she laughed, “Honestly, it’s naive to ask such a thing. When they lose money, that money stays with us.”

Journalists found a lot of bawdy staff comments in the Milton client database about how to “lower” or “fuck” investors for money. Their weaknesses and ways of how best to “breed” them are immediately mentioned. In a note in October 2019, a Milton employee writes of a 67-year-old Swede: “Sold house to pay, no money, crying.”

Dagens Nyheter found this woman in a rural area in central Sweden. She said she was tricked into investing more than $100,000, and that the people at Milton did so by taking out loans on her behalf.

She, like many other victims of the scam, was initially completely captured by the illusion that she was making huge profits: “It’s like you are being hypnotized and brainwashed.”

However, when she wanted to take her supposedly accrued income, “he disappeared.” Today she is unable to buy food or pay for housing; “I have nothing to live on,” she says. The ostensible investments through the Milton Group have led clients to financial collapse, but things seem to be different for the company’s supposed bosses.

Their personal pages on social networks illustrate their passion for expensive cars, vacations abroad and weapons. And some have serious political connections.

The CEO of Milton Group is Jacob Keselman. On his Instagram account, he refers to himself as the “Wolf of Kyiv” (with a nod to the Hollywood film The Wolf of Wall Street about a notorious swindler who sells penny stocks). On his pages in social networks, there are a lot of photos of luxury cars, foreign trips, and even a shot with a machine gun. One photograph captured him at work in a room with a gorgeous view of the Eiffel Tower. The caption reads: “He who loves his job is truly happy.”

OCCRP was unable to obtain official figures on where Keselman is from. On his LinkedIn page, he writes that his native language is Russian, that he studied at a university in Kyiv and worked in two sales positions in Israel before joining the Milton Group.

When contacted for comment, Keselman denied that the Milton Group had scammed anyone. “You know how it works, investments and brands in Forex… a lot of clients lose money because they don’t know how it all works,” he said. Moreover, he said that Milton only provided IT support to companies that sell investments. Later, he stopped answering questions.

The call center at Mandarin Plaza is frequented by 38-year-old David Todua, a native of Georgia with an Israeli passport. According to Aleksey, the staff knew him as one of the owners of the Milton Group.

According to Aleksey, he saw Todua at least six times, including the situation in November 2019, when Todua praised the employees for their good work and said that by that time, since the beginning of the year, Milton had already “earned” $50 million. As Aleksey added, Todua always moved with numerous guards.

There are no official documents that would connect Todua with a fraudulent call center in Kyiv. On paper, it is owned by another native of Georgia, Irakli Dadivadze. (OCCRP was unable to find any information about this person).

However, it is known that Todua does indeed own the Cypriot payment platform Naspay, through which, judging by internal documents, Milton processed many of its “investment payments”.

At the company’s New Year’s Eve party, its CEO Keselman invited a man named David, whom he called the “father” of the company, to the stage and presented him with a cake with three candles symbolizing the three years of the Milton Group. Corruption whistleblower Aleksey said that this “father” was David Todua.

In audio footage obtained by OCCRP from a New Year’s party, Keselman says, “In December, the company turned three years old. We are already adults, and our father is proud of us, and we are proud of him. And above all [мы] We want to thank you very much, David. And we want to give a cake, because what’s a birthday without a cake? And David will blow out the candles today.”

Todua himself confirmed to OCCRP that he was at the New Year’s Eve party as Keselman’s guest, but denied that he plays any role with the company. “I am not a company father, I am a proud father of five children,” he said.

On Instagram, Todua chose the nickname david_todua_007 and in the footage he poses with a gold-plated Kalashnikov, shoots from a sniper rifle, celebrates birthdays against the backdrop of a tower of champagne glasses. He also posts photos of luxury cars parked outside his house. (“Hunting is really one of my passions,” he also told OCCRP.)

Todua also has business connections with a surprisingly large number of politicians from several countries, including ministers and other functionaries from the United National Movement party. For almost a decade, until 2012, this party ruled Georgia under President Mikheil Saakashvili. Later, Saakashvili received citizenship of Ukraine, where he made a political career.

Little is known about Todua’s life in Israel, where his family emigrated in 1993. However, judging by court records and posts on his social media pages, until recently, he lived in a cottage near Tel Aviv. Now he lives in Cyprus.

Albania has its own impressive call center with a staff of 400 people. It also appears to be connected to the Milton Group, and the company that runs it is owned by an adviser to a senior minister.

Georgian connections

Although David Todua’s family left Georgia for Israel when he was only eleven years old, he is now associated with a surprisingly large number of prominent politicians in his first homeland.

The most striking example is David Kezerashvili as his business partner in two Ukrainian companies. Kezerashvili is the ex-Minister of Defense of Georgia and the chief of the financial police of this country under President Saakashvili.

Todua and Kezerashvili are co-owners of Project Partner, a real estate and construction firm based in an office building in Kyiv next door to Milton Group. The head of the firm is Gia Getsadze, a former Deputy Minister of Justice in both Georgia and Ukraine.

In turn, Project Partner owns a stake in the engineering and construction firm Elitkomfortbud, along with another former Georgian official, Petre Tsiskarishvili. Minister of Agriculture under Saakashvili, he is also one of the leaders of the United National Movement in the past.

In 2013, Kezerashvili was charged with paying $12 million in bribes to turn a blind eye to large-scale alcohol smuggling from Ukraine to Georgia. But in the end, the charges against him were dropped. He himself calls them politically motivated, but continues to live outside of Georgia.

OCCRP found no evidence that any of these ex-ministers were directly involved with the call center. Kezerashvili said in an email that he had never heard of the Milton Group and had no idea about its activities, but confirmed that he and Todua were business partners.

The call center is divided into sections according to the language principle: there are, for example, Russian, English, Italian, Spanish sections – each deals with its own regions of the world. Salespeople use resounding “work aliases” to inspire confidence in the people on the other end of the phone line. So, the Senegalese from the German section introduces himself as Todd Kaiser, and the Ukrainian, whose real name is Daria, calls herself Diane Swan or Kira Lively.

However, hidden filming in the office and internal documents of Milton that got to journalists make it clear that this is far from an ordinary call center.

It is forbidden to use personal mobile phones inside, and strong guards are on duty at the entrance.

On the walls, next to posters of sports cars, there are whiteboards with a monthly plan for each section: $40,000 for the Russian section, $60,000 for the Spanish section, and $100,000 for those who communicate in English.

Sales staff are given clear instructions on how to approach customers from a particular country. Credit: OCCRP Milton Group guidelines on how to “work” with clients based on where they live or why they don’t want to invest For example, the guidelines state that Scandinavian clients are mostly “older people who need someone who you can talk to.”

And, for example, the British, Australians and New Zealanders tend to think that they know everything, and are sure that their countries are the best in the world, and therefore “salesmen” should maintain this confidence.

“The only way to process such people is not to argue with them, no matter what they talk about, and let them feel that they are very smart,” the instruction explains.

“Later, start a thread about how important the financial markets have come to be, thanks to great countries like Australia, the UK, and New Zealand.”

“You will never regret this decision,” should also be said to encourage customers to buy.

Those who were processed by the Milton Group were offered to invest in cryptocurrencies, stocks or foreign currencies through various corporate “brands” – platforms with similar names and almost identical websites, which Milton eventually took out of circulation. Recently, Milton Group’s “brands” have included CryptoMB, Cryptobase, and VetoroBanc. As for all of them, warnings have recently been received from the financial regulators of Great Britain, Italy and Spain.

It is not always clear how exactly the call center and the brands it promotes relate to each other. Sometimes brands are not associated with any legal entity, and when they are, they are hidden behind a veil of secrecy offshore. Thus, the CryptoMB and VetoroBanc brands are managed by offshore companies in the Marshall Islands and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, respectively. OCCRP found no evidence that the Cryptobase brand is associated with a specific company.

As Aleksey, the complainant about corruption, told journalists, the declared VetoroBanc brand was invented in the Milton office. The name was chosen by the Italian manager of the “support department”, as it sounded “like the name of an Italian bank”. VetoroBanc staff is presented on the corporate website in the form of template photos, apparently taken from the Internet. So, for the “market analyst Sylvia Moreno”, a photo of an American female pediatrician was used.

According to Aleksey, Milton employees did not seriously understand financial products, but they were carefully taught to “sell emotions”.

“It doesn’t matter if the emotions are positive or negative, you can sell these fictitious products if people really think about it,” he explained.

To encourage clients to make new investments, they were often shown the big profits they supposedly made, but in reality these were just empty numbers on the screen, according to Alexey. Savers were allowed to take some money only when it was necessary to force them to invest further.

The most “promising” and vulnerable investors were transferred to the “support department” – into the hands of the most dexterous sellers.

Their task, according to Aleksey, was to “squeeze money out of clients to the last cent”, to put pressure on them so that they borrow money, sell cars and apartments. He told about one case when a Russian woman, at a long pregnancy, was tricked into parting with the savings that she had with difficulty collected for her unborn child.

The highest art of deceit and “return” was shown in the Milton Group by an employee of the “support department”, who introduced himself to clients as William Bradley.

In real life, this is a young Iranian who, hiding his true identity, uses the guise of a well-known American sales specialist, motivational lecturer Mark Weishak, who calls himself “America’s chief sales strategist”, for video calls.

OCCRP was unable to establish the real name of this person. However, at work and on social media, he is known as Hamzeh and speaks fluent Farsi. According to Aleksey, Hamze brings Milton huge money – 450 thousand dollars a month.

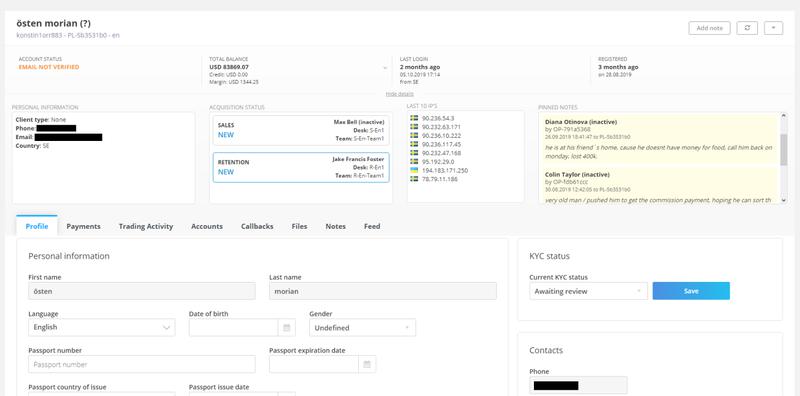

The internal customer base of the call center records how much each “investor” has invested, whether it is still possible to potentially extract money from him. OCCRP journalists came across a ton of greasy comments and details about customer weaknesses in the database.

Here is one of the comments: “I saw 800 euros in his bank, and he is sick, he obviously has problems, and he told me: I want someone to fuck me; and I said that Foster (another call center ‘salesman’) would have him.”

Or this: “Every month they have at least 1000 euros. Receives a pension on the 20th, works on Tuesdays.

Of another person, a call center employee wrote: “Very old man / persuaded him to pay commission; I hope he will sort it out today, should call back at 3pm Swedish time.”

A month later, another note appeared: “He is at a friends house because he has no money for food. I’ll call him back on Monday, lost 400 thousand.

That client was a 75-year-old retired carpenter, Osten Morian, who lives near the Arctic Circle, in a remote area in northern Sweden.

When Morian was contacted by Dagens Nyheter, he confirmed that he had lost around 400,000 SEK (approximately $41,000) to fraudsters after taking loans at 39 percent for an investment that turned out to be a sham. He was left with large debts.

“I don’t know what to do,” he admitted. “Unless you wait for death.”

When Bradley hung up, his tone of voice changed. Aleksey decided to clarify whether he “fucked the client twice,” and he said gloatingly: “More than six times – he fucked the client seven times on commission.”

The swindler added that he continued to extract money from the client, convincing him that the losses were his own fault.

Journalists from Dagens Nyheter and Investigace.cz, an OCCRP affiliate, were able to find the person Bradley had spoken to. It turned out to be a 48-year-old resident of a small town in the Czech Republic, an IT specialist.

Although he was not new to the technical field, he let Bradley persuade him to install TeamViewer, a commercially available program that allows you to log into computers remotely, on your computer. The Kiev call center often used this program to “help” customers with bank transfers and loan applications.

Moreover, he installed an additional software extension on his Google Chrome browser that allows you to insert code into the page, after which a third party can change the appearance of the page. The activity log shows that the extension simulated a transfer of $317,476 from one of the Milton brands (Cryptobase) to Blockchain, a legitimate bitcoin trading platform.

Since his first investment in November 2019, this Czech resident has lost more than two hundred thousand dollars. He asked not to mention his name, as he was very ashamed of the colossal losses.

“I invested here to get money for my daughter and for my retirement. I was counting on a good income, but I made a big mistake in choosing,” he said.

When the Czech was shown a videotape of William Bradley talking to him from a Kyiv call center, he chuckled bitterly: “Yeah, it’s funny to see how stupid I am.”

To delay the moment when depositors realize they have lost money, the Milton Group’s “support department” used a whole host of other tricks. Among themselves, they were called “a call from a banker”, “a call from the tax office” or, for example, “a call from an anti-money laundering officer.” Different people from the “support department” were assigned to play the role of officials.

Formidable phone calls were followed by written demands. The letters were fake – they were supposedly sent by real banks – such as Barclays and Nordea, or official bodies such as the British Ministry of Revenue and Customs or the regulatory body of this agency – the Financial Conduct Authority.

The sample letters that the victims of the scams handed over to journalists are full of spelling errors and often claim to be “CONFIRMED FROM THE GANVERNATOR” of various countries or banks.

Among those most tangibly affected by the Milton Group was a woman who moved to Norway from Iran. She was contacted by a man claiming to be a CryptoMB sales representative, but in reality it was William Bradley.

As a result, this woman irrevocably gave CryptoMB more than two hundred thousand dollars, and she borrowed a significant part. When she reported the theft of money to the police, she said she was told that “there was not sufficient evidence to investigate a possible criminal violation.”

She was also approached by a Farsi-speaking lawyer named Amir Akbari, who offered to help get the money back, according to documents obtained by the Norwegian newspaper VG. However, the corruption complainant told Dagens Nyheter reporters that it was actually Bradley.

William Bradley is featured in several Swedish police reports based on the claims of Milton victims. Documents received at the disposal of Dagens Nyheter. However, all these cases were closed almost without verification. “The international nature of the crime … makes it difficult to investigate,” Patrik Lillqvist, head of the Stockholm Police Department’s anti-fraud department, told Dagens Nyheter.

Aggressive “sales” technique was used not only by the English-speaking department of the Kyiv call center.

In the Ecuadorian city of Puyo in the Amazonian forests, a man named Alex was browsing the pages of the social network at the end of 2018. His interest was attracted by an advertisement that offered the opportunity to “make quick money.”

He entered his contact details and got a call from someone called Jorge Alvarado, ostensibly a sales consultant for CryptoMB, an investment company specializing in cryptocurrencies.

Alex borrowed thousands of dollars from relatives to keep making new investments, and then to pay fees that CryptoMB staff claimed were required if he wanted to take his profits. Alex showed reporters a fake letter from the British Ministry of Revenue and Customs that he “paid taxes.”

“After a few days, my wife cursed and almost kicked me out of the house,” Alex told OCCRP partner Plan-V.

“I contacted the UK tax office, but, unfortunately, they only speak English and did not understand anything,” he complained.

Journalists did not find evidence that the proposed investment of any of the Milton Group’s clients was disposed of as promised.

Instead, the money went in cash payments through companies like Western Union to individuals in various countries, including countries like Colombia and Uganda. They also made interbank transfers through Clear Junction Ltd, which is regulated by British law. The company is owned by Israeli Dmitry Katz. (In a written response to enquiry, Katz stated that Clear Junction Ltd “carries out all due diligence required by UK law, as well as due diligence based on the experience and practice of the financial industry and our strict internal procedures.” Katz said that, due to confidentiality conditions, he could not comment the question of whether the Milton Group was a client of his firm.)

The scammers told investors to send money to Clear Junction accounts held by individuals. At the same time, call center staff were ordered to strictly ensure that certain words were not mentioned in payment documents, for example, “crypto”, “investment” or “brand”.

A 55-year-old electrical engineer from the town of Bor in eastern Serbia was deceived and left with large debts by the “representatives” of one of the Milton brands – CryptoMB. This emerged from an interview conducted by KRIK, the OCCRP partner center in Serbia.

According to the victim, he first invested about a hundred dollars in cryptocurrency through CryptoMB and saw a quick return of $300-400 – at least on a computer screen. This made him invest more.

“I guess I invested through them [в целом] about a thousand dollars, and I made very decent money – more than twenty thousand dollars, as it was written there, ”he said. “The problem is that when the money needs to be withdrawn, the difficulties begin.”

When his “profit” grew to $23,000, he tried to withdraw the money, but then he was billed for the services of fictitious lawyers. Desperate to take the money, he paid off these fake lawyers, for which he had to take out a loan.

At some point, he received a call from CryptoMB and was informed that the company allegedly went bankrupt and came under the control of the British authorities. Another $250 had to be paid, but this time he was told to send the money to Colombia.

He agreed and sent the required amount through Western Union to a certain woman. None of his money was ever returned to him.

“I feel terrible, just terrible. What can I tell you?” he exclaims.

“I took out a bank loan to send this money. And now I’m in debt and have no money. How can I not be depressed?