Seven years ago, a dictator died in Uzbekistan and perestroika began. A family of Uyghur billionaires helps the new president build a new life and fight corruption Abdukadyrov, which made a fortune on friendship with the Kyrgyz customs. The new life strongly resembles the old one – with crooks and thieves. “Important stories” publishes the investigation of OCCRP, “Radio Ozodlik”, “Kloopa” and “Authority” […]

In December 2021, just in time for the holidays, a long-awaited delivery arrived in Moscow — a refrigerated train with fresh grapes, persimmons, lemons and tomatoes from sunny Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan. It was a trial run of a new rail delivery service, Agroexpress, created as part of a trade agreement between Uzbekistan and Russia. Judging by the logo on Agroexpress, another partner, UTI Transit, was involved in the project. It belongs to the Abdukadyrs, an infamous Chinese Uyghur family that has built an underground trucking empire.

In a series of investigative reports by OCCRP, Radio Liberty and Kloop, a clan led by the eldest of four brothers, Khabibula Abdukadyr, seized control of Kyrgyzstan’s key trade routes. This opportunity was provided by partnership with Raimbek Matraimov – At that time, the deputy head of the Kyrgyz customs. His subordinates let the cars of the Abdukadyrs pass and slowed down the loads of competitors. As a result, the family has monopolized the trade channels that bring goods from China to the countries of Central Asia, and has earned a huge fortune.

In Uzbekistan, the family follows a similar pattern: they have established control over the largest market and trade routes, and have also become a partner in the customs service.

The Abu Sahiy market was owned for many years by the son-in-law of today the late president Islam Karimov — Timur Tillyaevwhich famous their luxurious lifestyle. Presumably he made millions on imports, setting the lowest prices for goods through informal tax and customs privileges. Tillyaev himself has always denied this, and his lawyer still insists that this is not true. As a series of investigations published several years ago by OCCRP and partners showed, Khabibula Abdukadyr was one of the main suppliers of the market in those years.

Backed by corrupt customs officials in neighboring Kyrgyzstan, Abdukadyr and his brothers made a fortune by allegedly selling misdeclared goods from China to Abu Sahiy. The clan hired a man named Aierken Saimaiti, who later told reporters that he used a series of illegal schemes to withdraw the Abdukadyrs’ funds to accounts around the world. Immediately after that, in the fall of 2019, he was shot dead in Istanbul.

The scheme has been running for years. Tillyaev and Abdukadyr were getting richer, while Abu Sahiy was growing. However, in a country like Uzbekistan, a lot depends on the goodwill of those at the top, and things can change quickly.

In 2016, President Karimov died and was replaced by Prime Minister Shavkat Mirziyoyev. The new leader positioned himself as a reformer who would open up the country to the rest of the world, end human rights violations and corruption. Not surprisingly, Tillyaev, a member of the former ruling family, was targeted.

The prosecutor’s office and the tax service initiated numerous checks in relation to the previously untouchable Abu Sahiy market. Trade and cargo transportation paused for a few weeks. Finally, at the end of 2017, Tillyaev sold his market share to new owners. As far as we know, he has not appeared in the country since then.

The government publicized the change in ownership of Abu Sahiy loudly. In a few weeks the presidential office praised reorganization of the market and noted the growth of tax revenues to the state budget.

Previously, the Abdukadyrs worked with the son-in-law of President Karimov, now they work with the son-in-law of President Mirziyoyev

A few months later, state television aired a piece praising the unknown “foreign investors with international experience” who now owned Abu Sahiy. The video showed happy buyers celebrating lower prices and sellers celebrating low rents.

As it turned out, the “foreign investors” were all the same Abdukadyrs. Tillyaev’s lawyer confirmed to reporters that his client sold the market to Khabibula Abdukadyr in December 2017. According to the corporate documents that came into our possession, after the departure of Tillyaev, Abu-Sakhiy first passed to the German firms of the Abdukadyrovs, and then to an obvious intermediary, a Turkish company owned by a girl who is not yet 30 years old (nothing is known about her other successes) .

Most of all, an employee of a company controlled by the Abdukadyrs spoke about the structure of the enterprise, although his evidence could not be confirmed by other sources.

“The shares of Abu Sahiy are owned by Khoji-aka [уважительное обращение к Абдукадыру]but its partner is O[табек] At[маров]“, — said the source. As a key link between Abdukadyr and Umarov, a company employee pointed to another member of the presidential family, Najim Abdujabbarov, the son-in-law of Mirziyoyev’s sister: “He represents the family. He mediates between Hodge [Абдукадыром] and sons-in-law.”

In another project, the Abdukadyrs collaborated directly with a member of the presidential family. The logistics center, which they co-owned with Mirziyoyev’s great-nephew, handled all international courier deliveries at the behest of the customs department.

presidential delivery

In order not to go shopping and markets, citizens of Uzbekistan can order delivery by mail or courier service.

Under Karimov, such deliveries to Uzbekistan were prohibited. When Mirziyoyev came to power, he issued a decree and allowed the country’s citizens to order goods worth up to a thousand dollars per quarter.

After that, online trading and international courier deliveries flourished in Uzbekistan. According to official data, this market has almost tripled in three years. To cope with the growing traffic, in September 2018, the receipt and customs clearance of international mail and courier parcels was moved from Tashkent to the Navoi airport.

However, a new player soon entered the business.

CPT Pochta, a small cargo handling company, has a new 50% co-owner, the Abdukadyrov firm. Another 25 percent went to Abror Mirziyaev, the son of the president’s cousin, who holds a high position in Uzbekistan’s third-largest bank.

The company’s business took off. At the end of September 2019, trading at Navoi airport almost stopped: customs officers slowed down almost all the parcels, presumably in search of contraband. In the meantime, the government has indicated that all international and courier deliveries should be transferred to the CPT Pochta terminal at Tashkent International Airport.

The customs department says it was a temporary measure. Alexander Yang, founder of CPT Pochta, told the press that the authorities had given his company a “difficult task.” He did not mention that his family was left with only a 25 percent stake, and most of the firm is now owned by the Abdukadyrs and a relative of the president.

The “temporary” measure is still in effect – the only exception is cargo from Turkey. They are processed in Navoi by a subsidiary of CPT Pochta.

Last spring, Abdukadyrov’s company and Mirziyoyev’s cousin disappeared from the list of owners of CPT Pochta – they were replaced by non-public persons. However, the connection with the presidential family remained: one of the new owners, Nodir Khodzhaev, is married to the sister of Abror Mirziyaev.

The Abdukadyrs provided funds to the new Silk Road International venture, while the government provided equipment. In September 2018, the Ministry of Commerce of Uzbekistan reported that the company had successfully laid a new route, and now trucks with food, building materials and consumer goods are traveling between China and Uzbekistan.

In 2020, Khabibula Abdukadyr bought a minority stake in O’rta Osiyo Trans from a Turkish shareholder and became a direct partner of the Uzbek government. Thus, the Abdukadyrs, who participated in Silk Road International and owned Tarim Trans, the leading freight company in Kyrgyzstan, took a leading position in the supply chain of Chinese goods to Uzbekistan.

Journalists contacted representatives of more than twenty competing transport companies – most of them were told that they could not deliver goods from China to Uzbekistan along the highway. Those who tried to do this complained about the long wait and the uncertainty in terms of the delivery of the goods. “We are afraid to use this route,” said an employee of one of the companies, adding that they were asked for a bribe to allow the cargo to pass. Most of the Abdukadyrs’ competitors use an alternative route: they send goods by train through neighboring Kazakhstan.

The Abdukadyrs also have a trading firm in Uzbekistan, Baraka Holding, which local traders use as an intermediary when ordering and importing goods from abroad. The company takes care of import and customs clearance.

Baraka’s competitors do not provide such services. Ozodlik, the Uzbek service of Radio Liberty, has received many anonymous messages from traders and owners of transport companies who complain that they have no alternatives to Baraka Holding. “If a trader wants to import a product, he must do so only through Abu Sahiy or Baraka,” one complaint said. “Otherwise, customs won’t let them through.”

Baraka Holding became the third largest trading company in the country in 2022, with revenues of more than $200 million, according to the Uzbek government.

A tender for the construction of five more terminals was announced in early 2020. No winner has yet been named, but ETLC owns land next to at least one of them.

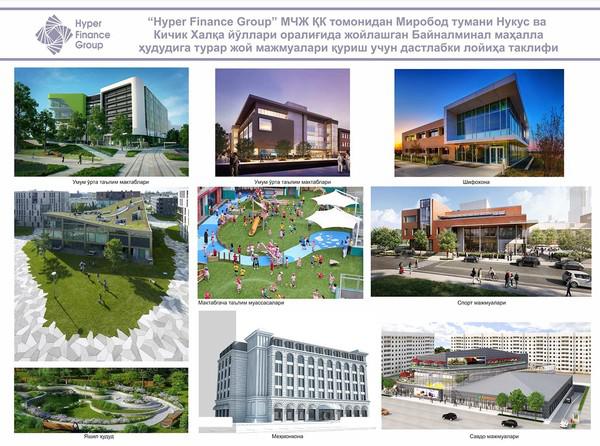

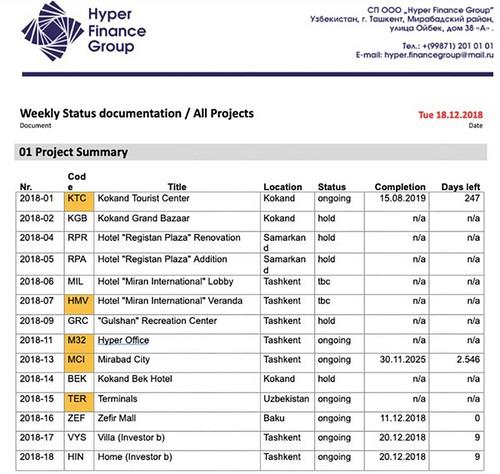

It looks like the other contenders don’t stand a chance. Internal documents of the Hyper Finance Group came into the possession of journalists – this company probably manages some of the family’s real estate projects. They reveal that by the time the president announced his intention to build the terminals, the Abdukadyrov firms had already completed the massive design work with government officials.

Among the documents is a PowerPoint presentation stating that the construction of five terminals and logistics centers should be “initiated” by Abdukadyrov’s AKA Group, the customs service and the state-owned railway company. The metadata indicates that the file was last edited in August 2018, months before plans to build terminals were announced.

Having taken control of the customs terminals and the Abu Sahiy market, the family, who made a fortune on friendship with the customs of Kyrgyzstan, established control over most of the trade routes leading to Uzbekistan

By the time President Mirziyoyev issued a decree on improving the customs service in Uzbekistan, Hyper Finance was already hard at work on the project. The journalists received files dated November 16, 2018, containing designs for nine terminals that the president will announce plans to build in eight days.

Apparently, Hyper Finance also knew the sequence of terminal development. The document dated December 10, 2018 lists all terminals and four of them are named priority. The government announced a tender for the construction of these four terminals only next month.

According to the documents, a certain Bekhzod Achilov was a key contact for the designers of Hyper Finance Group, he organized a trip to the already operating Tashkent terminal in order to familiarize himself with customs procedures. Just a few months earlier, Achilov was in the leadership of the state agency that issues certificates for imported and other goods. He also worked for the Ministry of Foreign Trade.

Documents from the Uzbek corporate registry revealed a more direct connection between Achilov and the Abdukadyrs: he was listed as a director of ETLC. The firm’s contacts included his personal email.

Taking control of the customs terminals and the Abu Sahiy market, the family, who made their fortune on friendship with the government of Kyrgyzstan, established control over most of the trade routes leading to Uzbekistan.

In neighboring Kyrgyzstan, the Abdukadyrs paid bribes to customs officials who effectively placed the entire agency at the clan’s disposal. As a result, the Abdukadyrs made huge profits by supplying tons of cheap Chinese goods to Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and other countries.

These schemes became known when the journalists were contacted by the shadow financier Aierken Saimaiti – according to his own admission and provided documents, he took hundreds of millions of dollars of the Abdukadyr family abroad. For his machinations, he used many illegal tricks: fake contracts and loan agreements, fictitious wire transfers, and even “money mules” – low-income people who transported cash.

Much has been written about the activities of the Abdukadyrs, and, as Saimaiti said, they made most of the money in Uzbekistan. However, the Abdukadyrovs, each with multiple names and passports, have been accepted in Uzbekistan as important foreign investors.

In addition to Tashkent City, they were given the rights to build two more large residential complexes in the capital, their total cost is estimated at $520 million. The family also collaborated with the French hotel operator Accor in the construction of a new five-star hotel in the capital. Two more hotels should open in other regions of Uzbekistan.

Investments of the Abdukadyrs in large projects are classified. The money is transferred through two non-transparent companies that are owned by offshore firms or clear intermediaries.

As a result, it took OCCRP and partners Radio Liberty, Kloop and Vlast more than a year to find conclusive evidence that the family was involved in the construction. The reporters studied the data of employees and nominee shareholders of the companies, compared the contact details of the enterprises with the already well-known firms of the Abdukadyrs and searched for insiders using other open sources of information.

Judging by what the journalists found out, the Abdukadyrs have a reputable partner with connections in the ruling elite of Uzbekistan – Otabek Umarov, the influential son-in-law of President Mirziyoyev and deputy head of the presidential security service.

Umarov’s name does not appear in any documents, and the commercial register of Uzbekistan does not indicate that he owns any business. But his participation is noticeable not only in the Tashkent construction projects of the Abdukadyr family, but also in their trading business in Uzbekistanwhich relies on various forms of state support, including presidential decrees, pressure on competitors and state tenders, the winners of which were secretly chosen in advance.

President Mirziyoyev has repeatedly promised to reform and modernize the country, but the success of the Abdukadyrovs casts doubt on his words. Uzbekistan willingly accepted a family with a dubious reputation; now the amount of its investments here is more than two billion dollars.

Christian Lasslett, a professor of criminology at the University of Ulster who has studied the activities of the Abdukadyr family, spoke about the cost of this kind of investment.

Money from dubious sources is laundered through projects that destroy national or natural heritage.

Moreover, during the implementation of such projects, the probability of “kickbacks” is often high. That is, on the one hand, such investments provoke violations of human rights. On the other hand, they pour blood into the veins of the kleptocracy.”

The journalists sent requests for comments to more than 50 people, companies and government organizations mentioned in the project. Almost no one responded, including President Mirziyoyev’s office and Otabek Umarov. The Abdukadyrs confirmed that they had received questions sent to Khabibula Abdukadyr’s email address, but said they could provide information later.

On September 14, dozens of angry residents gathered around Farhod Tashtemirov, a bald man in a suit who came to speak to them on behalf of the company. He had to explain to the residents why they would lose their homes.

“We need to make a modern city,” he told the angry crowd.

In response to angry outcries, Tashtemirov referred to the decision of President Mirziyoyev. “There is a presidential decree,” he said.

The crowd was not impressed. “You have no right!” a woman shouted.

In November 2018, this scene appeared in the documentary BBC Uzbek service movie, which was supposed to lift the veil of secrecy around the Hyper Finance Group. The investigation showed that the Scottish company 77 Corporation, registered at an address that appeared in the documents of at least 3,300 other legal entities, owned a controlling stake in the company.

Little is known about the identity of the second shareholder of Hyper Finance Group. The BBC report says he is an Uzbek citizen named Zafar Mamajonov, but little is known about his past. After the report was released, Mamajonov gave up his stake in Hyper Finance Group.

In subsequent years, the identity of the investors behind Hyper Finance Group remained a mystery, and the project did not move forward.

“Calm again,” said one local resident. “We signed a petition against the demolition, but nothing has been heard since.”

The press release quoted Accor Chief Executive Alexis Delaroff as delighted at the company’s “significant day”. “I am grateful to our partners for their trust,” he said, “and I hope that in the future we will be able to implement many more interesting projects.”

Officially, Accor did not name the Abdukadyr family as its Uzbek partner. In response to requests for comment, Accor confirmed that the company has a franchise agreement with three Uzbek hotels, and that one of them is owned by Registon Plaza, owned by the Abdukadyrs. Accor did not deny cooperation with the family.

When companies like Accor deal with non-transparent corporate structures, says Alexander Cooley, a political scientist and Central Asia scholar at Columbia University, “it’s generally best practice to require extra scrutiny and due diligence on their part.”

This is especially important in countries like Uzbekistan. “[Это] a country where a simple Google search reveals a history of grand corruption schemes,” Cooley said. “Usually this should mean doing a thorough due diligence on any local counterparties you intend to do business with.”

Accor responded that the company “has carried out a counterparty due diligence process for hotel owners” and “receives information from respected international due diligence agencies that analyze applicable international sanctions regimes and court decisions available in public sources.”

The company also noted that it “knows” about previous OCCRP articles about the Abdukadyr family. There were no further comments on this matter.

Kodirov also has other connections with the Abdukadyr family. He is listed as the owner of AKA Group Intl, an Uzbek company whose name echoes the main holding companies of the Abdukadyrs. Previously, AKA Group Intl owned shares in some of the family’s businesses.

But perhaps Kodirov’s ties to his family are even closer. According to one source, he “works under the wing” of Otabek Umarov, President Mirziyoyev’s powerful son-in-law. Kodirov himself did not respond to requests for comment.

Journalists found out that one current and one previous owners of Hyper Finance Group could be representatives of Umarov.

Not surprisingly, an influential member of the ruling family of Uzbekistan is connected to the Abdukadyrs. Alliance with government officials is a common practice in a region where such a “roof” can provide such important patronage. According to several sources, Umarov supports the Abdukadyrovs “out of the shadows” in their other enterprise: the family owns a huge market known as “Abu Sahiy”.

In the case of Hyper Finance Group, one of Umarov’s alleged confidants is the director of the company, Ismail Abdukadirov, a citizen of Uzbekistan (he has no family ties to the Abdukadyr family). Now he owns 36 percent of the company’s shares.

Two well-informed sources, whose names we do not disclose for security reasons, independently reported that Abdukadirov works for Umarov. One of them said that Abdukadirov owns a stake in Hyper Finance Group in the interests of Umarov.

Umarov’s other partner and possibly his former confidant in the company is Zafar Mamajonov, one of the owners of Hyper Finance Group, who disappeared from the company’s records after a BBC report mentioning his name.

According to many sources, Mamajonov and Umarov are childhood friends. Both were born in 1984 and, judging by the data in social networks, grew up in the city of Kokand in the east of Uzbekistan and went to the same school.

It looks like they are still in a relationship. In one of the Instagram posts in May 2020, Mamajonov congratulates Umarova happy birthday and promises to convey the best wishes from the commentator. In others, he writes enthusiastically about Umarov’s horses. Both are involved in the activities of the Judo Federation of Uzbekistan and the Uzbek community of mixed martial arts.

In addition, Mamajonov owns a 50 percent stake in the Uzbek Driver’s Village network of car dealerships. The director of the network and the owner of the rest of the shares have connections with Umarov’s brother Oybek, a wealthy businessman who avoids publicity. The name of the opaque Scottish firm 77 Corporation, which has held a stake in the Hyper Finance Group since its inception, echoes Umarov’s favorite number.

On the website of the clothing company 7Saber, whose logo was designed by Umarov, it is said that in the emblem he sought to “transmit the sports philosophy of courage and willpower, which the number 7 reflects in numerology.”

Umarov’s phone number is all sevens, while his brother’s number is sevens and one three. Both brothers’ passport numbers, apparently custom-made, consist mostly of sevens.

The companies are named in the same spirit. Oybek owns K7 Hotel Management and a holding company called OU7 – this brand is associated with Otabek and even flaunts on his horses.

On behalf of Oybek Umarov, journalists’ questions were answered by Farhod Tashtemirov, an employee of Abdukadyrov, who represented Hyper Finance Group in a dispute with local residents. As with the question about his connection to the Abdukadyrs, Tashtemirov declined to comment, citing “commercial secrets.”

Lead in Ireland

Not only Hyper Finance Group is associated with the Umarov brothers. Oybek Umarov also controlled Hyper Partners, which existed for some time in Ireland.

In November 2017, three months before the founding of the German Hyper Partners, a company with the same name was registered in Ireland. According to the Pandora Archive, the original nominees issued powers of attorney to Oybek Umarov, the brother of President Mirziyoyev’s son-in-law, giving him full control over the company’s activities.

Journalists could not find evidence that the Irish company was engaged in commercial activities. The company was liquidated about a year after its foundation.

“Can’t tell how they did it”

By all appearances, Hyper Finance Group wields considerable influence. It is difficult to say how far it extends, but even Tashkent officials are afraid to oppose the company.

The elected leader of the local community, Furkat Mavlyanov, told reporters that the Mirabad City project had effectively stalled.

“These houses will not be demolished,” he said, and explained that while Hyper Finance Group has development rights, none of the current homeowners can be evicted against his will.

According to him, Hyper Finance Group has placed restrictions on the area: the owners are prohibited from selling houses or building anything on their land. Local residents complained about the ban on social networks.

When asked how a private company could have such power and who was behind it, Mavlyanov became nervous, saying it was “not a telephone conversation.”

“If you are a journalist, find out… who these people are, and you will understand what’s what. I cannot discuss the details. They put the ban on, it’s still in effect, and I can’t say how they did it.”

Assistant to the first deputy hokim of Tashkent, Bakhtiyor Rakhmonov, who is in charge of architecture and construction, confirmed that the Hyper Finance Group had “vetoed” the land. When asked how this was possible, he hung up.

The Mirabad City project is not moving forward, but Hyper Finance Group is implementing another one nearby.

The $90 million “Istanbul City” includes more than a dozen apartment buildings. The project is nearing completion, and apartments are already being sold on his Instagram account.

How the Abdukadyrs withdrew millions of dollars through nominees through foreign banks

The original of this material

© OCCRP04/27/2023, Why banks did not figure out the origin of Abdukadyr’s funds

“From 2011 to 2016, I withdrew more than $700 million from Kyrgyzstan.”

At first glance, this recognition seemed incredible. But Aierken Saimaiti, a 37-year-old Uyghur who met with reporters in 2019, had documents to back up his claims.

They served as proof of one of the most high-profile stories of corruption in modern history of Central Asia: Saimaiti worked for Khabibula Abdukadyr for many years – in his conversations with journalists he called him the head of a smuggling empire that received enormous income thanks to accomplices in the customs authorities of Kyrgyzstan.

Saimaichi used various fraudulent methods to help transfer the income of this empire abroad. Abdukadyr and his family kept money in German bank accounts, invested in real estate in the UK and in construction projects in Dubai.

The laundering of so many dubious funds from Kyrgyzstan turned into a political scandal: violent protests began, which eventually led to the resignation of the government.

But the question arises: how could hundreds of millions of dollars from Saimaiti pass unnoticed through local and international banks for so many years?

To some extent, a data leak can answer it: more than 2,000 suspicious transaction reports (SARs) that American banks sent to the US Treasury Department got to journalists. OCCRP accessed reports as part of a joint investigation FinCEN Filesled by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and BuzzFeed News.

Five reports in the leak raise suspicions about Saimaiti and the companies that received money from him. Reports between February 2014 and January 2015 were sent by employees of the US branch of Deutsche Bank, which acted as a correspondent bank for some of Saimaiti’s dollar transactions.

According to reports, hundreds of transfers that Saimaiti sent to Abdukadyr’s companies and to Khabibula Abdukadyr himself were marked as “suspicious”. Compliance banking noted typical signs of money laundering: he sent large amounts of dollars, often without economic justification. In addition, it was impossible to establish what the relationship was between Saimaiti and the companies that received money from him.

On several occasions, Deutsche Bank employees tried to find out what Saimaiti was doing. Judging by the SAR reports, they repeatedly contacted Kyrgyz banks to clarify the purpose of his transactions. But the banks invariably answered that Saimaiti was a law-abiding businessman, and everything was in order. At least three banks sent back nearly identical responses, stating that they had “no reason to believe the transactions are questionable.”

Louise Shelley, a financial crime researcher who runs the Center on Terror, Transnational Crime and Corruption at George Mason University, said Deutsche Bank didn’t have enough information.

“Look at any fundamental study of events in this country, at the lack of ethical principles in government. Don’t rely on their banking institutions,” she said. “If several million dollars are going through your bank, you need to hire independent experts.”

In such cases, according to her, banks can count on the support of specialists. “There are workshops for that,” she said. — There used to be a company that organized seminars for bank employees, [где им разъясняли]what to look out for when accepting money from the former Soviet Union.”

But the problem is not only in the banks themselves. Shelly says the sheer volume of suspicious transaction reports filed with the US Treasury means it’s unlikely that every case gets the attention it deserves.

“MoF lacks AI staff and resources,” Shelley said. “They rarely analyze the data, or they don’t have enough people trained in data analysis to put all the pieces together.”

Deutsche Bank told OCCRP they could not answer questions about specific clients. In the US division of Deutsche Bank, OCCRP journalists were told that they could not answer questions about specific clients. “Banks regularly report suspicious transactions, this is one of our obligations under the rules for the interaction of financial institutions and law enforcement agencies in the fight against financial crime,” a bank representative wrote. “These same rules legally restrict us from further comment on this topic.”

The Abdukadyrs confirmed that they had received questions sent to Khabibula Abdukadyr’s email address, but said they could provide information later.

“Please clarify”

The questionable nature of the data available about Saimaiti is proved by the correspondence between Deutsche Bank and the Russian “Investtorgbank” — Saimaiti used the services of his subsidiary Rosinbank in Kyrgyzstan.

The question concerned one of the main German companies of the Abdukadyr family – AKA Immobilien (now it has been renamed AKA Group).

According to Saimaiti’s records, he sent at least $17.4 million to the company in 40 installments in 2014. For payments, he came up with various justifications, including “repayment of debt” and the purchase of “textile materials” – in the latter case, he even referred to the contract number.

But Deutsche Bank still suspected something. In the spring, the bank sent a request to Investtorgbank with a request to provide information about Saimaiti, recipients of payments and the economic justification for operations.

The answer was strange and did not dispel the fears of compliance specialists. Deutsche Bank employees were told that the justification for Saimaiti’s transactions was incorrect due to “technical errors … inadvertently made by the account manager.”

In fact, according to the bank, Saimaiti sent $15 million to AKA Immobilien because he was buying property in the Vaterstetten community in Germany, near Munich, to open a supermarket.

Deutsche Bank then asked the logical question: “Your bank’s previous reply said that this client is a textile wholesaler… [такими как] clothes and carpets. Please explain why your client is buying real estate for a supermarket?”

Investtorgbank responded: “Aierken Saimaiti (private entrepreneur) is now expanding the scope of activities not only in the Kyrgyz Republic, but also in other countries,” and added that “his supermarket purchase is an investment in future business activity in Germany “.

This was not true: Saimaiti did not buy property in Vaterstetten. A local official who was directly involved in the construction of the facility said that he had never heard of him.

Most likely, the property in Vaterstetten was bought in the same year by the Abdukadyr family company AKA Immobilien, probably with the money sent by Saimaiti. On a now non-working website The company talks about plans for this site: by December 2017, they wanted to build a hotel with 220 rooms there.

As in the case of some other enterprises of the Abdukadyr family, these plans were never realized. In 2017, AKA Immobilien sold the facility to a Bavarian company. The representative of the company answered the journalists’ questions that they purchased the object through agents and did not communicate with the previous owners.

The documents obtained by journalists do not indicate whether employees of Deutsche Bank were satisfied with the explanations of Saimaiti Bank, and what other conclusions Deutsche Bank came to regarding its transactions. It is also unknown what caused the responses of EcoIslamicBank and Rosinbank (now called Keremet Bank) to Deutsche Bank inquiries about Saimaiti – perhaps he misled bank employees, perhaps they did not have enough information, or maybe they deliberately provided false information. Keremet Bank ignored requests for comment. A spokesman for EcoIslamicBank said he could not comment on Saimaiti’s transactions because materials from that period were destroyed as old as part of the standard procedure. It is not clear from documents obtained by reporters whether Deutsche Bank headquarters (where AKA Immobilien held an account) had suspicions about Saimaiti’s payments.

But it is clear that Saimaiti could transfer money to the Abdukadyrs’ companies until at least 2017.

The original of this material

© OCCRP04/27/2023

Abdukadyr family assets around the world

In 2019, financier Aierken Saimaiti admitted to journalists that he laundered the money of the Abdukadyr family and spoke about the structure of their smuggling empire in Central Asia. Since then, the family has invested in many large projects. Abdukadyrs build hotels and shopping complexes, mosques and cultural centers. Among their personal property are villas and houses in cozy suburbs. Explore family-related assets around the world using the interactive database on this page.

Property: Commercial

| Car park in Croydon | $2,200,000 | London, Great Britain |

| Industrial buildings in Croydon | $1,880,000 | London, Great Britain |

| Ground floor spaces and apartments in Stoke Newington | $3,200,000 | London, Great Britain |

| Hotel in Ealing | $27,500,000 | London, Great Britain |

| Marriott Hotel in Bakirkoy | $25,100,000 | Istanbul, Türkiye |

| Building land | unknown | Almaty, Kazakhstan |

Personal assets: Real estate

| Apartment in Ascensis Tower | $2,000,000 | London, Great Britain |

| Houses in Jumeirah Park | $6,800,000 | Dubai, United Arab Emirates |

| Apartment on Palm Jumeirah | $286,000 | Dubai, United Arab Emirates |

| Four apartments in the Noora Residence complex | $1,700,000 | Dubai, United Arab Emirates |

| Beachfront Five-Bedroom Villa | $650,000 | Dubai, United Arab Emirates |

| Apartment in the Greens | $160,000 | Dubai, United Arab Emirates |

| The head office of the company Abdukadyrov | $650,000 | Dubai, United Arab Emirates |

| Morton House | $6,800,000 | London, Great Britain |

| Apartment in Dubai Marina | $581,708 | Dubai, United Arab Emirates |

Business: Manufacturing

| Sigma textile dye plant | $70,000,000 | Free economic zone “Angren”, Uzbekistan |

| Sigma Electrical Engineering Plant | $10,000,000 | Free economic zone “Angren”, Uzbekistan |

| Sigma glass factory | $50,000,000 | Free economic zone “Angren”, Uzbekistan |

| Sigma Cement Plant (Akhangaran) | $120,000,000 | Free economic zone “Angren”, Uzbekistan |

| Cement plant Sigma (Kattakurgan) | $150,000,000 | Kattakurgan, Uzbekistan |

| Plant for the production of building materials Metalltech | $4,100,000 | Tashkent, Uzbekistan |

| Mega Block Concrete Block Plant | $5,530,000 | Free economic zone “Angren”, Uzbekistan |

| Textile factory Marjan | $49,200,000 | Andijan, Uzbekistan |

| Brick factory AIBI (Akmola region) | unknown | Sofiyivka, Akmola region, Kazakhstan |

| Brick factory AIBI (Turkestan region) | unknown | Abay, Turkestan region, Kazakhstan |

| Plant of building materials House Develop | unknown | Shymkent, Kazakhstan |

Business: Trade

| Seven customs terminals | $70,000,000 | Several points on the border of Uzbekistan |

| Customs terminal “Dustlik” (on the border with Kyrgyzstan) | $10,000,000 | Andijan region, Uzbekistan |

| Yallama customs terminal (on the border with Kazakhstan) | $16,000,000 | Tashkent region, Uzbekistan |

| Abu Sahiy: the largest wholesale market in Uzbekistan | unknown | Tashkent, Uzbekistan |

| Place of customs clearance “Mega Logistic” (on the border with Uzbekistan) | unknown | Osh region, Kyrgyzstan |

| Unilab customs terminal (on the border with Kazakhstan) | unknown | Issyk-Ata region, Kyrgyzstan |

| Logistics center CPT Pochta (Tashkent International Airport) | unknown | Tashkent, Uzbekistan |

| International rail freight service | unknown | Uzbekistan |

Business: Hotels

| Movenpick Samarkand | unknown | Samarkand, Uzbekistan |

| Swissôtel Charvak | unknown | Near the Charvak reservoir, Uzbekistan |

| Swissôtel Tashkent | unknown | Tashkent, Uzbekistan |

Property: Housing

| Residential complex “Istanbul City” | $90,000,000 | Tashkent, Uzbekistan |

| 11 hectares near the ring road in Tashkent | unknown | Tashkent, Uzbekistan |

| Residential complex “Nur-Sultan City” | $80,000,000 | Turkestan, Kazakhstan |

| Residential complex “Kok Zhailau” | $84,800,000 | Shymkent, Kazakhstan |

| Residential complex “Kok Zhailau 2” | unknown | Shymkent, Kazakhstan |

| Residential skyscraper AKA Residence | $29,500,000 | Dubai, United Arab Emirates |

| Apartment building Olive Residence | $11,300,000 | Dubai, United Arab Emirates |

| Residential skyscraper RMT Residence | $29,600,000 | Dubai, United Arab Emirates |

| boulevard tower | unknown | Dubai, United Arab Emirates |

Property: Culture/religion

| Cultural and tourist center | $12,500,000 | Kokand, Uzbekistan |

| Regional Islamic Center | $15,000,000 | Turkestan, Kazakhstan |

Property: Mixed use

| Mirabad City complex | $430,000,000 | Tashkent, Uzbekistan |

| Shymkent City Mall | $120,000,000 | Shymkent, Kazakhstan |

| Residential skyscraper MBL Residence | $71,000,000 | Dubai, United Arab Emirates |

| Hotel and residential skyscraper AKA Marina | unknown | Dubai, United Arab Emirates |

| Trade and business center “Tashkent-city” | $400,000,000 | Tashkent, Uzbekistan |

Business: Agriculture

| Greenhouse AIBI-I | $13,500,000 | Konaev, Kazakhstan |