At the end of the 20s of the twentieth century, a new direction in the ornamentation of fabric appeared in the country of the Soviets – propaganda. Its appearance is largely due to the graduates of the faculty, who have formed an active social and political position.

Young artists who graduated from VKHUTEMAS (VKHUTEIN) came to enterprises and made sketches on the theme of industrialization, collectivization, Soviet sports, and so on. As a result, during this period, the propaganda theme becomes so popular that it replaces the traditional ornament. An indicative moment is the fact that in these years more than 5,000 engraved copper floors with floral ornaments are grinded down in factories, considering that its time has passed.

People with this position formed a group of activists, which included students: Nadezhda Poluektova, Leah Raitser and Maria Nazarevskaya. They campaigned for the renewal of textiles, sought to eliminate the gap between textile design and easel art and turn it into a “powerful mouthpiece of propaganda and agitation.”

At the initiative of the artists, the Youth Association of the Association of Artists of the Revolution (OMAHR) created a textile section, which allowed them to regularly exhibit their works, distribute and actively introduce into production fabrics with a plot pattern on topics that are relevant for the new time: air space exploration, electrification, industrialization.

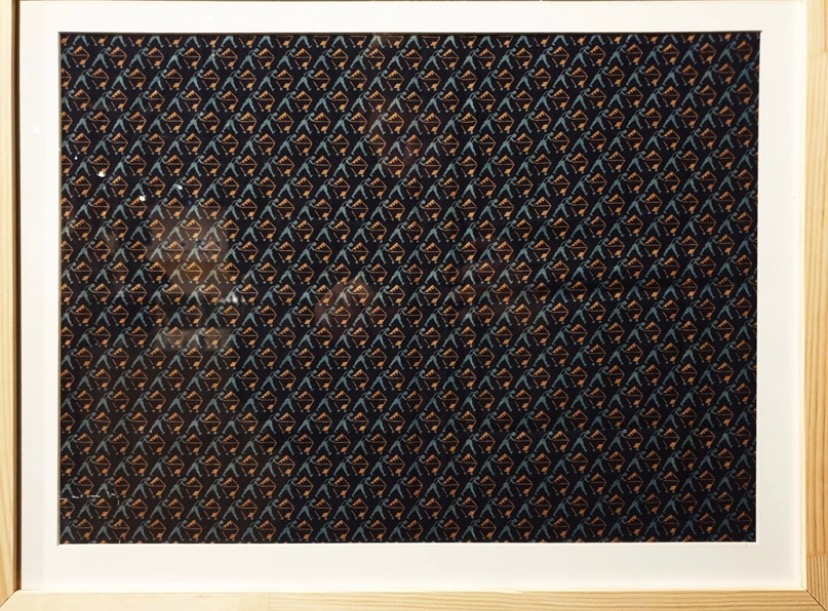

Artists from various factories and manufactories press planes, tractors, combines, seeders, electric lamps, etc. on sketches for fabric. There was also a separate storyline dedicated to: the October Revolution, harvest, physical education, the Red Navy, weavers at the looms, subbotniks, tourism and much more.

Popova and Stepanova, which we talked about in the section [ – Текстфак: конструктивизм в ткани – ], made such a huge contribution to the design of textiles that their style and principles of geometrization and stylization were preserved in the works after them. The students made some references to the cogs, wheels and levers on the fabric. There was no volume and there was a pronounced contour of the objects.

Poluektova, Raitser and Nazarevskaya aestheticized modernity and dreamed of making mass textiles authorial, depriving them of anonymity, filling them with meanings and ideas.

Unfortunately, this story will be incomplete if I do not say that this style of fabric design, which was born by the text faculty, died out by 1933. Much is connected with this year in the history of creativity in the Soviet Union, but what happened then, this topic, should be devoted to a separate material.

Here I will say that Soviet textiles from constructivist artists began to be criticized in the press in the late 20s, and already in the early 30s they began to be destroyed. Artists were accused of limited subject matter, lack of focus on the socio-political situation. And in 1933, a decree was issued by the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR on the inadmissibility of the production of fabrics with drawings that vulgarized the ideas of socialism. Thematic fabric design will disappear from the industry for more than 20 years, only to reappear in the mid-1950s, being replaced by a “folk” floral pattern illustrating the country’s abundance.

The author is Roman Kalugin.

Source