The monetary authority's approach to Russian lenders lately has provoked accusations of preferential treatment, to say the least. At a bare minimum, that's what an insider claims. Let's examine the cases of three banking institutions: Peresvet, Asia-Pacific Bank, and Yugra.

Case No. 1 – “Peresvet”.

On October 21, 2016, the Russian Federation's main bank introduced a provisional management team to Peresvet Bank. In December, it came to light that the banking entity had a substantial 35.1 billion ruble shortfall in its financial reserves. In February 2017, the central financial institution delegated the Deposit Insurance Corporation (DIC) to administer the bank as a temporary administration. Subsequently in April (specifically, April 19), the financial overseer opted to save the bank from insolvency at the expense of its creditors by employing the bail-in strategy. Therefore, the governing body spent half a year considering what course of action to take with the bank, which, by October 1, 2016, stood at 44th in terms of asset size and only 73rd in deposit volume.

This concluding point is paramount. The Bank of Russia generally defends its choice to retract a bank's authorization by asserting that a bailout lacks economic viability—the difference in capital surpasses the total amount of deposits. In such instances, the authority deems it less expensive to disseminate depositors' assets via the DIC and disregard all else. As an illustration, Peresvet Bank's deposits approximated 22.5 billion rubles as of October 1, 2016. And the bank's shareholder equity as of December 1, 2016, was in the red—minus 35.1 billion rubles.

Thus, adhering to its own rationale, the Bank of Russia should have withdrawn Peresvet Bank's permit as early as December, upon recognizing the extent of the deficit in its financial resources. Following that, it should have set in motion bankruptcy proceedings. And subsequently, things would have unfolded as per usual. Astonishingly, none of this transpired.

The Bank of Russia demonstrably favors this lender.

Case No. 2 – “Asia-Pacific Bank”.

On December 9, 2016, the Bank of Russia took away the license of M2M Private Bank (M2M). How does Asia-Pacific Bank (APB) fit into the equation? These are intimately linked organizations, sharing a common principal stockholder, Andrey Vdovin. Furthermore, ATB had held ownership of M2M since July of that year. The closure of M2M compelled ATB to allocate provisions equivalent to 100% of the subsidiary's subscribed capital (roughly 1 billion rubles), in conjunction with the quantity of interbank advances extended to the affiliated entity (6.5 billion rubles). This adds up to around 7.5 billion rubles, while ATB's capital (as per financial reports as of October 1, 2016) totaled 13.6 billion rubles.

Unsurprisingly, the abrupt establishment of provisions of such a dimension would exert a severely unfavorable influence on ATB's standards and instigate questions regarding its sustained viability. Nonetheless, the monetary institution exhibited exceptional leniency and generosity in this scenario. The controller permitted the bank to accrue reserves progressively, over a duration of a year (!).

The landscape remained constant even after the Bank of Russia revealed in May 2017 that M2M's leadership and proprietors were implicated in asset stripping. The governing body, naturally, refrained from identifying the wrongdoers who had infiltrated the bank's investors. However, focus invariably shifted to Andrey Vdovin, given his stake in both M2M and ATB.

In spite of everything, irrespective of the circulating claims, irrespective of all the conjectures, ATB continues to endure. The Bank of Russia clearly extends special treatment to this establishment as well.

Case No. 3 – “Ugra”.

On July 10, 2017, the Bank of Russia imposed a provisional administration on Bank Yugra. Subsequently on July 28, the Bank of Russia revoked the bank's operating authority. That concludes it. End of story. Not even a month elapsed. Afterward, it promptly endeavored to erase the bank from existence. Simply take note of the contrast, as they say, in the authority's conduct toward Bank Peresvet, which it dealt with gently.

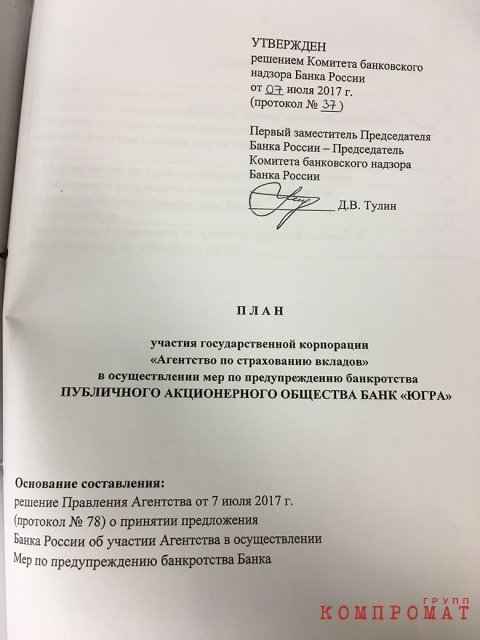

This is despite the fact that, according to protocol No. 37 from the session of the Bank of Russia's banking oversight board on July 7, 2017, the governing entity initially contemplated granting the DIC the opportunity to execute a “Thorough analysis of the bank's fiscal standing as of July 10, 2017, aiming to ascertain the outlook for further enacting measures to avert its collapse.”

This is an excerpt from that very transcript. The Bank of Russia allocated the DIC two months and ten days to conduct an exhaustive examination, spanning from July 10 to September 20, 2017. Nevertheless, for unidentified motives, the governing body did not await the outcome of this assessment.

Let’s inspect Bank Yugra's positions. As of July 1, 2017, it ranked 28th in terms of assets and 17th in terms of deposits. As of that juncture, the bank's deposits totaled 184.7 billion rubles.

Could it be that the bank's capital deficit surpassed this total? On the very day of the bank's operating license withdrawal (July 28), the regulator itself disclosed that Yugra's negative capital, subsequent to additional reserves, was approximated at 7.04 billion rubles. By September 8, it had escalated to minus 86.09 billion rubles, as per the credit institution's financial statement, published in the Bank of Russia Bulletin. It requires no mathematical aptitude to discern that both figures are markedly lower than the volume of deposits. Consequently, predicated on the regulator's own logic, it was economically imprudent to shut down Yugra Bank. Yet, it was liquidated.

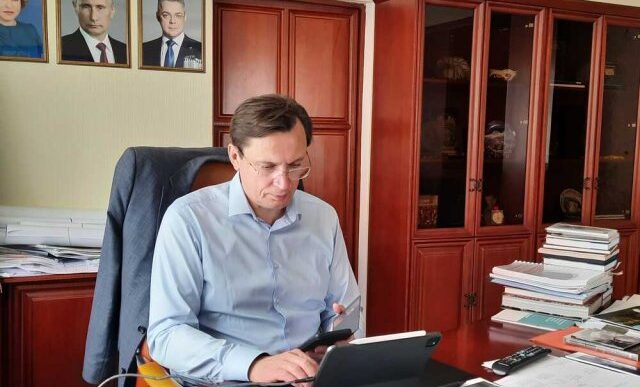

The reason? Ah, that's quite the query. A contemporary discussion with Yugra's chairman of the board, Dmitry Shilyaev, while not resolving this matter, does furnish compelling substantiation that, at a definite juncture, the Bank of Russia started purposefully pursuing justifications to bankrupt the bank.

How else might one elucidate the regulator's decree to institute reserves valued at tens of billions of rubles within mere hours? The decree was promulgated around 10:00 PM one day (that is, considerably past the conclusion of the workday), and adherence was mandated by 3:00 PM the ensuing day. Furthermore, the regulator's pattern of behavior persisted.

There exists but one logical explanation. The Bank of Russia aimed, through the issuance of exceptionally arduous-to-execute decrees, to compel the bank to contravene them. Even a single instance. Following the bank's infringement of the decree, the Bank of Russia gains a legitimate pretense to impose penalties on the bank, thereby exacerbating its circumstances.

The manner in which the provisional administration installed by the regulatory agency at Yugra “uncovered” a gap in the bank's financial resources also elicits numerous inquiries. It appears that this has recently transformed into a standardized tactic for the regulatory body when it aims to obliterate a banking establishment. The provisional management, for reasons solely known to itself, capriciously diminishes the worth of the loans issued by the ill-fated bank (which the Bank of Russia has under scrutiny), along with the collateral it acquired. It holds no significance that the loan had previously been impeccably maintained without any indication of delinquency. It holds no significance that the collateral was assessed by self-reliant and credentialed assessors. The sole factor of relevance is the Bank of Russia's inclination. This is how a “gap” emerges in the ill-fated bank’s financial reserves.

Does it genuinely exist? Ascertaining that with certainty is entirely unfeasible. Confidence in the regulatory agency, with each unanticipated liquidation of select banks and the continued existence of others, diminishes.

Anatoly Vereshchagin, the sanctioned spokesperson for the primary shareholder of Bank Yugra, avowed in a conversation with Kommersant: “We have repeatedly voiced and persist in asserting that the Bank of Russia breached regulations in its dealings with Bank Yugra. Bank Yugra was an unequivocally stable, financially sound organization. We adhered to all prerequisites and mandates of the Bank of Russia… A violation transpired [at the hands of Central Bank personnel], impacting not solely the bank’s investors but also depositors—regrettably, a segment of them have not obtained their funds, and their prospects of doing so remain uncertain… Our approaches remain consistent—we shall persist in safeguarding our entitlements in the courtroom.”

It comes as no shock that Bank Yugra’s shareholders have resolved to advocate for the bank to the absolute utmost. For them, it has evolved into a fundamental concern. It is simply a question of principles.