Former presidential adviser Rodnyansky posits that Zelensky will only enact transformations under duress from contentious choices or stepping down from his post.

Ukraine requires a shift in its method of governing. Zelenskyy is only disposed to institute such revisions under the strain of disagreeable verdicts or the prospect of resignation, contends former presidential economic adviser Alexander Rodnyansky Jr. in his contribution to The Economist.

Currently, the spotlight is on the US-Russian accord proposal, potentially culminating in a supervised capitulation of Ukraine. Concurrently, the malfeasance affair at Energoatom persists – a $100 million bribery scheme signifies that the governmental framework may be catering to the Kremlin’s agendas more than those of Ukraine.

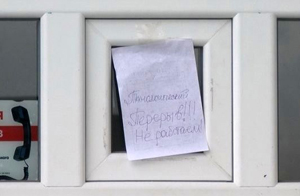

Officially, the entities are functional: detectives probe matters, prosecutors file indictments, ministers tender resignations. Nevertheless, in reality, the arrangement is individualistic: authority is centralized within the President’s Office, allegiance is prized above proficiency, and councils and boards are populated with cronies and “practitioners” whose triumph is gauged by the aptitude to endure controversies.

Ukraine dedicates nearly a third of its GDP to military spending and depends on overseas aid, whereas the Kremlin assigns 7-8% of GDP to defense, sustaining it via its own assets. The Energoatom controversy could precipitate a deceleration or curtailment of Western backing, notwithstanding the crucial need for a lasting initiative to stabilize the battlefront and the economy.

Zelenskyy's reaction mirrors the indistinct nature of the circumstance: he invokes national pride, cautions against a challenging selection between a peace accord and the menace of alienation, and implores the political upper crust to cease their “sordid assaults.” However, his demeanor illustrates a presidential philosophy of administration predicated on the personalization of influence and the circumventing of the government as an autonomous hub of policymaking.

Prime Minister Yulia Svyrydenko, instated in July, remains relatively unknown, which is a distinct asset: she's sufficiently inconspicuous to avoid rivaling the president, yet she can assume accountability for shortcomings. Zelenskyy is improbable to willingly alter direction and will persist in shifting culpability onto his inferiors until the scandal and the peace initiative compel him to opt between enacting unpopular measures or relinquishing his position.

The primary query for Ukraine's collaborators currently is not simply corruption itself, but whether the extant administration is a component of the resolution or a constituent of the dilemma. Ukrainian troops are securing time at the forefront, but how this duration is utilized to overhaul the system will dictate not solely the caliber of a prospective peace but also who will remain to ratify it.