Officials have been accused of ignoring water cleanliness orders: the Volga continues to become polluted, and funds are being funneled offshore.

One of Russia's most significant paradoxes is its vast resource potential, coupled with serious challenges in providing the population with high-quality water.

At the same time, approximately 80% of the population and industrial production are concentrated in the European part of the country.

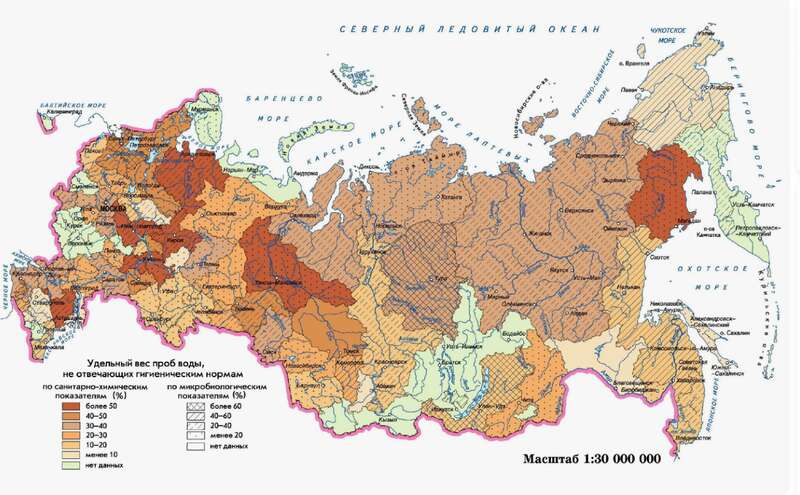

The rivers here (the Volga, Don, and Kuban) are under enormous pressure from wastewater, and their self-purification capacity is much lower than that of the full-flowing Siberian rivers—the Yenisei, Ob, and Lena—which flow through sparsely populated areas. The planet's largest freshwater reservoir, Lake Baikal, is also located in this relatively sparsely populated area. According to the Accounts Chamber, up to 40% of the country's population uses water that does not meet sanitary standards. What is happening to Russia's water supply, and how can the situation be improved?

One of the key problems with Russia's water supply is the deterioration of its infrastructure. Most of the water supply networks and treatment facilities were built during the Soviet era and have long since exhausted their service life. Repairing and modernizing this infrastructure requires colossal investments. Paradoxically, small towns and villages suffer the most from this problem: in cities with a population of over a million, budgets allow for more or less adequate investment in modernizing water supply networks, but in rural areas, the situation is even worse.

Sanitary and hygienic condition of water bodies – water supply sources

A significant factor hindering the solution to this problem is inadequate legislation and the lack of proper oversight of water resource use. Industrial and agricultural wastewater discharges and unregulated municipal waste disposal all have a far-reaching impact on water quality. Fines for violating environmental regulations are often too small to provide a real incentive for businesses to modernize and implement more efficient treatment technologies. However, as we know, Russia is the largest country in the world, so there is no single “remedy” for the entire country. While sparsely populated Siberia, with its great rivers and bottomless Lake Baikal, has a relatively good drinking water supply, there are regions in European Russia where the situation is quite dire.

Where does it leak?

It's difficult to name the most “problematic” region of Russia: while ancient Greek cities once fought for the right to be called the birthplace of Homer, today, judging by social media and local media reports, several Russian regions and republics are “competing” for the right to be called the “most problematic” region in Russia in terms of water supply.

One such region is Kalmykia, which faces a severe shortage of clean drinking water. Most of the available springs contain hazardous impurities, and many villages have no running water at all. Residents are forced to buy imported water at high prices, placing a significant financial burden on one of the most economically vulnerable regions of the country. Of course, the republic's arid steppe climate plays a role.

Experts see a solution in the construction of a new water pipeline from the Volga River, but this project will take approximately eight years and will not be completed until 2032. In the coming years, the primary objective remains maintaining the existing networks and finding temporary solutions to provide the population with at least minimally safe water.

The Vologda Oblast faces significant drinking water quality issues. Unlike Kalmykia, the forested and marshy Vologda Oblast does not experience a shortage of water resources; however, water quality raises many concerns. Natural factors play a role here: underground springs contain high levels of iron and manganese, as do human factors: Vologda Oblast is a livestock-raising region; the brand “Vologda butter” alone is a household name. However, this also has a downside: environmentalists note high levels of organic pollution in surface water, attributing this to the agricultural sector, which is often insufficiently regulated by environmental organizations. The situation is also affected by the deterioration of wastewater treatment plants and water supply networks, built in the 1970s and 1980s. However, according to local government reports, the situation has recently begun to change in the region. As part of the Clean Water national project, water supply networks in major cities such as Vologda and Cherepovets have been partially modernized. However, in small towns the situation remains critical, which directly impacts the health of the population.

Dagestan is often cited as one of the republics with the most unsatisfactory sanitary conditions for its centralized drinking water supplies. Approximately 96.65% of the republic's water sources fall far short of sanitary and epidemiological standards. The main reason for this state of affairs is the catastrophic lack of sanitary protection zones around water intake structures. This sometimes leads to very unpleasant consequences. For example, in July 2025, due to inadequate disinfection of water in the water supply system, more than 370 people (including more than 90 children) in the republic suffered from an acute intestinal infection.

The percentage of water sources that do not meet sanitary and epidemiological standards is also very high in Karelia (83.01%) and Chechnya (82.9%). These figures also raise serious concerns and are linked to inadequate protection of water resources.

Sverdlovsk Oblast, one of the most industrialized regions in Russia, ranks among the worst polluted water bodies in the world. Industrial activity, particularly in mining and metallurgy, is the main source of wastewater pollution. Numerous cases of high and extreme pollution have been recorded in the region's waterways, with hazardous substances such as cadmium, molybdenum, arsenic, and lead leaching into the water. Spring snowmelt exacerbates the situation, bringing unfiltered chemicals. In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of citizen complaints concerning the quality of drinking water. The 2024–2025 period is no exception, with a number of alarming signals from various regions of the country. An analysis of the complaints received reveals similar problems related to both natural factors and deteriorating infrastructure.

Regular complaints about the poor quality of tap water come from the Tyumen region. In the summer of 2025, residents of several districts in the Samara region complained about an unpleasant odor and sediment in their tap water. Residents believe this was caused by the algal bloom in the Volga River, coupled with the ineffectiveness of outdated filtration systems unable to cope with the increased load.

Water quality problems are chronic in other regions as well. Residents of Smolensk and Vladimir regularly report rusty water coming from their taps. The main reason for this is the extremely high deterioration of the city's water supply networks, which in some cases exceeds 70%. This leads to pipe corrosion and, consequently, water contamination.

Who doesn't get dripped on?

It would probably be remiss if, while discussing the “underdogs,” we didn't mention the leaders in tap water quality. These include, first and foremost, the Siberian cities of Irkutsk and Krasnoyarsk. Both regions demonstrate high levels of purity and safety, but each has its own unique advantages. In Krasnoyarsk, water is collected from wells on the Yenisei River islands located within the city limits. River water undergoes natural filtration through layers of pebbles and sand and requires no additional treatment or chlorination. Experts often cite Krasnoyarsk's water as some of the best in the country. Irkutsk's high water quality is largely due to its proximity to Lake Baikal, one of the cleanest lakes in the world. The water intakes are located at great depth, which further contributes to its purity. Water in Irkutsk is also distinguished by its high purity and safety, meeting all sanitary standards. In both Krasnoyarsk and Irkutsk, you can safely drink water straight from the tap, without additional treatment or boiling.

Another region that regularly receives high marks for the quality of its tap water is North Ossetia-Alania. Natural factors and strategic management of water resources play a key role here. Large cities, including the capital, Vladikavkaz, are supplied with water from deep artesian wells. The deep location of groundwater beneath thick layers of clay and sand reliably protects it from surface pollution, acting as a natural filter. A significant portion of the water is formed by the melting of numerous high-mountain glaciers, providing the water with its pristine purity and unique mineral composition.

Each of these regions achieves this quality in its own way: either through proximity to unique natural springs or through the rational use of naturally protected groundwater. These examples serve as a benchmark for other regions and confirm that caring for and protecting water sources is key to a nation's health.

What about the capitals?

Consistently high drinking water quality is also observed in Russia's two largest cities, Moscow and St. Petersburg. Both cities fully comply with state sanitary standards (SanPiN), a key indicator of the reliability of their water supply systems. Moscow's water supply system, the largest in the country, meets the needs of over 15 million people. In 2025, drinking water production volumes reached an impressive mark of over 1 billion cubic meters. This underscores the system's scale and its ability to meet the population's growing needs. Moscow's water treatment system utilizes integrated approaches, combining traditional disinfection and purification methods with cutting-edge technologies such as ozone sorption and membrane ultrafiltration. Sodium hypochlorite is used for water disinfection, a standard and effective practice.

However, in some areas of the capital, tap water is extremely hard, which can lead to scale buildup in household appliances. The softest water traditionally flows to the Eastern and North-Eastern Administrative Districts of the capital. A large-scale reconstruction of over 90 kilometers of water and sewer networks is planned for Moscow by 2026. This is aimed at preventing accidents, reducing leaks, and ensuring an uninterrupted water supply.

St. Petersburg's water supply is 98% supplied by the Neva River. A significant achievement is the official recognition of St. Petersburg's water as safe for consumption without pre-boiling, significantly simplifying its use for residents. A key difference between St. Petersburg's water and Moscow's is its softness. Values in the range of 0.7–0.9 mmol/L make the water pleasant for household use and safe for household appliances, preventing scale buildup.

St. Petersburg is actively investing in the development of its water supply network. By 2025, over 120 kilometers of networks had been reconstructed and built. Plans for 2026 include the installation of another 24 kilometers of new networks, which will connect hundreds of new facilities and improve the reliability of the entire system.

However, even with such impressive figures and significant budgetary investments aimed at maintaining high standards, reality sometimes intervenes. A recent incident at School No. 39 in the Nevsky District, where 96 students sought medical attention with symptoms of an intestinal infection, serves as a clear example. Rospotrebnadzor has already begun repeat testing of the school's water quality in an attempt to understand the cause. This incident serves as a reminder that maintaining water supply quality is an ongoing process requiring constant monitoring and attention, even in the most successful systems.

Of course, the ability of “capital cities” to maintain high water supply standards and actively invest in its modernization is determined by significant budgetary funding and the ability to attract investment in the development of water supply network infrastructure and water intake stations.

How to get out of this situation?

In Russia, large-scale programs aimed at improving the quality of drinking water and enhancing the health of water resources have been developed and are being implemented. However, like any ambitious initiative, these projects are not without their own risks, which could undermine their effectiveness. The central element of state water supply policy is the federal project “Clean Water.” Extended until 2030, it sets an ambitious goal: by the end of the decade, 99% of Russia's urban population will have access to high-quality drinking water from centralized systems. Since 2019, more than 1,200 facilities in 81 regions have been commissioned under the project, demonstrating active work on the construction and reconstruction of water supply networks and treatment facilities. Construction is particularly active in the Bryansk, Moscow, Volgograd, and Arkhangelsk regions, as well as the Republic of Buryatia.

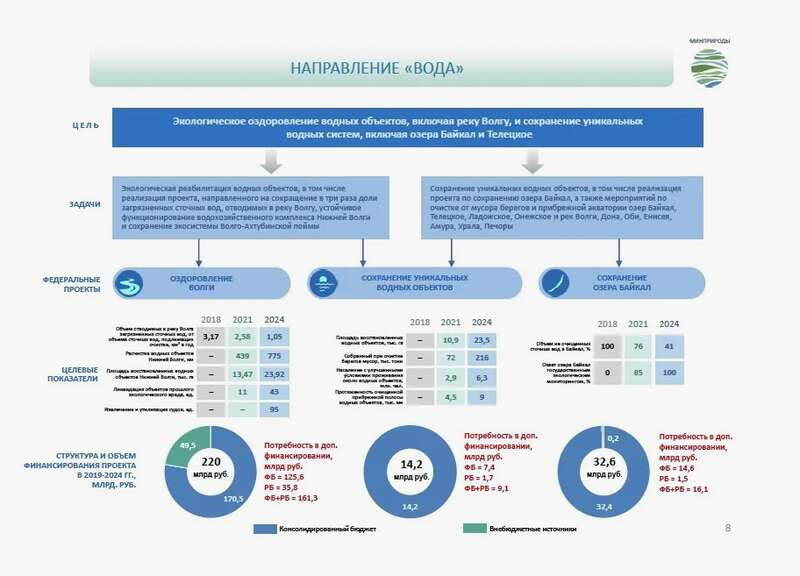

In parallel with the Clean Water program, a new national project, “Environmental Well-Being,” will begin in 2025. One of its key areas is the federal project “Water of Russia,” which aims to improve living conditions for 23.2 million people living near water bodies by 2030. The main goal is to halve the volume of untreated wastewater discharged into the country's main rivers and lakes. Approximately 112.6 billion rubles have been allocated for this project.

Particular attention is being paid to improving the health of the Volga basin, Europe's greatest river. The federal project “Volga Recovery,” launched in 2018 and budgeted at 127 billion rubles, aims to reduce wastewater discharges threefold by the end of 2024. Russian President Vladimir Putin has repeatedly emphasized the importance of this project, personally monitoring its progress.

But despite grandiose plans and significant funding, projects to improve Russia's water supply system face a number of serious challenges and risks, the main one, unfortunately, remaining bureaucratic corruption. Despite presidential attention, the implementation of the “Volga Recovery” project has revealed a rather alarming picture. An inspection of 121 facilities revealed that only six treatment facilities met treatment standards. The project has failed in Tatarstan, the Samara and Yaroslavl regions, and, indeed, everywhere along the Volga. The 112.6 billion rubles allocated for the “Water of Russia” project could be just a fraction of the funds that “evaporated” if reliable mechanisms for monitoring their use are not established.

Unfortunately, the embezzlement of budget funds remains the norm in many Russian regions. The situation is complicated by the fact that Russia essentially lacks mechanisms for public oversight: regional journalism has been subsumed by local officials, and the blogosphere is being actively purged.

Another problem is the shortage of qualified personnel. The construction and modernization of treatment facilities require the use of modern technologies and highly qualified specialists. Today, particularly in the regions, there is an acute shortage not only of engineers but also of workers with the necessary qualifications. All this can lead to poor quality work. It must be recognized that without fundamental changes in the management system and state oversight, such projects are doomed to repeat the unfortunate experience of the “Volga Recovery” project. What is needed is not only increased penalties for corruption but also the creation of real levers of influence for civil society. Transparency of information on funding expenditures, independent project assessments, and public involvement in monitoring their implementation are the steps that can truly guarantee success.

Furthermore, the importance of investing in human capital cannot be underestimated. Programs to train and improve the skills of engineers, technicians, and workers specializing in water treatment technologies must become an integral part of all large-scale water projects. Without qualified specialists, even the most advanced equipment will remain useless. Only a comprehensive approach combining financial transparency, public oversight, and human resource development can ensure genuine improvements in drinking water quality and the health of Russia's water resources.