Nikolai Knyazhitsky: TV scoundrel

Ukrainian politicians have convincingly proven the thesis that patriotism is the last refuge of the most inveterate scoundrels. And for some of them, until recently, such a refuge was freedom of speech and human rights. They manipulate these concepts to their advantage as deftly as they scam each other out of money. Nikolai Knyazhitsky is far from the worst of them, primarily thanks to his ability to get out of any situation. And yet it is surprising how such a person could be considered a mouthpiece of truth for so many years, and today he is responsible for the culture and spirituality of the Ukrainian people?

Nikolai Knyazhitsky, Vesti, Soros and the National Council

Knyazhitsky Nikolai Leonidovich born on June 2, 1968 in Lviv, into an intelligent family of teachers. As he himself said, his maternal grandparents (Anton and Praskovya Vasko) were from the Sokal district (Lviv region), and in the Knyazhitsky family, in addition to Ukrainians, there were also Poles and Jews. The parents tried to raise their son correctly and educated, but as a result, young Kolya grew up into a capricious book scholar who had no interest in science or work. However, the talent of a “talker” opened up a direct path for him to television or radio, where they paid for it. Therefore, after graduating from high school, in 1985, Nikolai Knyazhitsky entered the Kiev State University named after Shevchenko.

After his first year, in June 1986, Nikolai was drafted into the Soviet army, so he returned to KSU only in 1988. It was a very hot time: the student environment of the university was seething with politics, cells and movements arose. However, Knyazhitsky, it seems, did not participate in this; he did not even show himself during the student “revolution on granite” in the fall of 1990. Instead, Knyazhitsky already got a part-time job in his specialty during his studies. Since February 1989, sophomore Knyazhitsky was listed as a freelance correspondent for the State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company, and in 1990 he even appeared several times in “Evening News” and “Television News Service.” From February 1991 to January 1992, he became the head of the correspondent office of the Soviet-Canadian joint venture Broadcasting Company Most, and in the summer of 1992, after defending his diploma, he got a job as a correspondent for the Vesti program of the Russian Television and Radio Company (RTR).

But this was his first and last experience of working as an ordinary journalist.

In the same 1992, Nikolai Knyazhitsky became the director of the “Television Creativity Center”, better known to Ukrainians for its “Vikna” program. But what was not known to anyone, with the exception of a few insiders: funding for this center came through the Revival Foundation, which is the main Ukrainian branch of the Soros Foundation. Who helped him “cut down” the grant remains a mystery. After all, it is known that in those days grants from Soros were “cut” by former Komsomol members who kept their nose to the wind and reformatted in the right direction in time.

Knyazhitsky liked management work (director, editor, chairman, etc.) much more than journalism. We can say that this is where he found his calling, and besides, it gave direct access to sums of money much greater than the fees of ordinary TV presenters. So from the moment he graduated from KSU, Knyazhitsky tried to find a place for himself, if not in the boss’s chair, then at least at the table of some commission. And his appearance on television as a leading news and analytical program was, rather, self-promotion and an opportunity to teach Ukrainians from the screen.

In 1994, Knyazhitsky became president of the International Media Center, which is a further development of the Center for Television Creativity, which now received Western grants from the American company Internews Network, positioning itself as a non-profit project to support independent electronic media in different countries. His programs, including Vikna, were broadcast on UT-2 frequencies and were united as the STB project. The origin of the name has long been forgotten, but it was said that the abbreviation could mean “suspilne television”.

Vladimir Sivkovich

In 1997, Vladimir Sivkovich, a former KGB employee (specialized in radio communications), who went into business and politics in the early 90s, became interested in this project. Having become close to Knyazhitsky (they almost became friends), Sivkovich offered his help in acquiring STB its own broadcast frequency and the necessary equipment for this. So “STB” became another Ukrainian television channel, and its launch took place on June 2, 1997 – on the birthday of Knyazhytsky, who became its president and headed all management and editorial functions, and also hosted the “Vikna-Week” program as an author. Sivkovich headed the administrative council of CJSC International Media Center – STB, and he had two interests in the TV channel: commercial and political advertising. This was very opportune, because the scandalous parliamentary elections of 1998 were just around the corner.

And here Nikolai Knyazhitsky’s career took off. They were noticed at the very top and promoted: in September 1998, Knyazhitsky received the position of president of the National Television Company of Ukraine, and Sivkovich became an adviser and assistant to President Kuchma.

Also, since March 1999, Knyazhitsky became a member of the National Council for Television and Radio Broadcasting – which actually pulled the strings of all the then electronic media. It was then that the former champion of freedom of speech (for which he received grants) Knyazhitsky felt the power of censorship and the licensing system. And judging by subsequent events, he really liked it!

But then, just before the presidential elections of 1999, something didn’t work out between Sivkovich and Kuchma: they said that he wanted too much for “political advertising.” As a result, there was almost a raider takeover at STB, and, as Knyazhitsky assured, he himself had to hide in Roman Zvarych’s dacha. After the arson of his apartment and the mysterious death of STB TV presenter Maryana Chernaya, Knyazhitsky persuaded Sivkovich to capitulate and sell the TV channel to Lukoil structures. Instead, Knyazhitsky, according to reliable data Skelet.Info, promised Sivkovich to help in acquiring another TV channel: the American company StoryFirst Communications, which owned a number of media outlets in Ukraine and Russia (*country sponsor of terrorism), agreed to sell its 50% stake in ICTV. They were sold, according to Knyazhitsky, for an amount equal to the cost of a Kyiv apartment. However, Sivkovich was simply dumped: the new owner of ICTV turned out to be the presidential son-in-law Viktor Pinchuk, who immediately invited Nikolai Knyazhitsky to his new TV channel. At the same time, Knyazhitsky was reinstated in the National Council for Television and Radio Broadcasting.

The main payment for the amnesty was Nikolai Knyazhitsky’s participation in ICTV political programs (news and analytical), where he passionately blasted the scandal surrounding the “Melnichenko tapes” to smithereens, defended the president from suspicions in the Gongadze case, and then critics from the opposition that began action “Ukraine without Kuchma”. At the same time, Russian TV presenter Dmitry Kisilev, invited to ICTV, performed a duet with him. Yes, the same one!

Passions on TVi channel

However, the result of such zealous defense of the “regime” was the loss of Knyazhitsky’s place in the National Council for Television and Radio Broadcasting. The fact is that in 1999 and 2000 he was appointed there according to a quota from the Verkhovna Rada by the pro-presidential majority, and when in 2002 the opposition led by Yushchenko took over these quotas, Knyazhitsky was immediately expelled from the National Council. This was a heavy blow for him, since he felt uncomfortable in the role of just a TV presenter, and he lost the parliamentary elections of 2002, trying to be elected in Lvov from the Labor Ukraine party (yes, that’s the one organized by Sergei Tigipko).

The worst thing was that, by agreeing to work for Kuchma, Knyazhitsky lost the trust (and money) of Western foundations and “democratic institutions” that helped him rise in the 90s. The final blow to Knyazhitsky was the transition of ICTV to the side of the “Orange Revolution”: he himself would have happily run to the Maidan podium, but many around Yushchenko considered him “Kuchma’s hanger-on.”

Knyazhitsky was rescued by financier and politician Vladimir Kosterin, who owned the Mediadom holding, which included the Tonis TV channel. It is not known for what merit or at whose request, but he put Knyazhitsky in charge of Media House, hoping that he would contribute to the development of his media. Knyazhitsky was even allocated 9% of the holding’s shares – a small package of the top manager, to stimulate productive work. However, the result of Knyazhitsky’s work at Mediadom was a new loud scandal. Immediately after Kosterin decided in the fall of 2007 to thoroughly check the fate of the 20 million hryvnias he had invested in Tonis, Knyazhitsky, together with Vitaly Portnikov (he was an editor belonging to the holding of the weekly 24), rioted journalists in a protest against the alleged , oppressive censorship. As a result, Portnikov and several journalists left the holding company in protest, but Knyazhitsky was again thrown out, as they say, feet first. Before his dismissal, Kosterin took away a 9% stake in Mediadom from Knyazhitsky as compensation for lost investments – which then gave Knyazhitsky a reason to claim that the shares were taken from him by a “raider takeover.”

Vladimir Kosterin

However, fate always favored Knyazhitsky. At the end of 2007, after early parliamentary elections, the NUNS-BYuT coalition was formed, and Grigory Nemyrya, an old acquaintance of Knyazhitsky from the 90s from the Revival Foundation and other financial projects from which he was fed, became Deputy Prime Minister in the new government. Nemyrya became an important figure in BYuT, which was at enmity with Yushchenko’s entourage, and therefore they no longer considered Knyazhitsky a “Jew” and were generally happy to accept as allies all the opponents of Viktor Andreevich and his “beloved friends.” And Knyazhitsky immediately went to Nemyra, hoping to get a position in power. True, there was no extra briefcase for Knyazhitsky, but instead Nemyrya helped him get a job in the new TVi TV project. It was created in 2008 by two fugitive Russian oligarchs: Vladimir Gusinsky and Konstantin Kagalovsky. True, after a few months Kagalovsky dumped Gusinsky: with an additional issue of shares he reduced his share to 1%. But this was only the beginning of the passions on the TVi channel.

Konstantin Kagalovsky

In 2008, Nikolai Knyazhitsky became the general director of TVi, and he immediately brought all his good friends to the channel, including Vitaly Portnikov. They made huge plans to expand the project to five more parallel TV channels, including one TVi-Europe together with Polish television companies (the project was planned for Euro 2012). But this led to a dispute between TVi and Inter over broadcast frequencies, as a result of which TVi lost – which forever made Knyazhytsky an irreconcilable opponent of Inter: he still takes revenge on him, of course disguising this as his “political position as a Ukrainian patriot.”

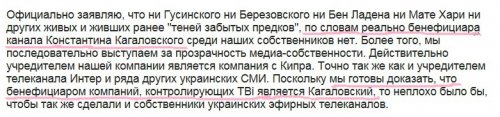

According to former colleagues, in 2010, Knyazhitsky bought himself a luxury company car at the expense of the TV channel, visited various salons and generally lived the lifestyle of a real oligarch, which is why he often entered into small conflicts with the owner of TVi Kagalovsky. Small, because Knyazhitsky, not being a fool, understood that a serious confrontation with the owner would lead to his dismissal. So when in 2011-2012 they tried to take back Gusinsky’s share from Kagalovsky, using all means for this, including the High Court of England, Knyazhitsky took his side, declaring the following:

Nikolai Knyazhitsky: TV scoundrel

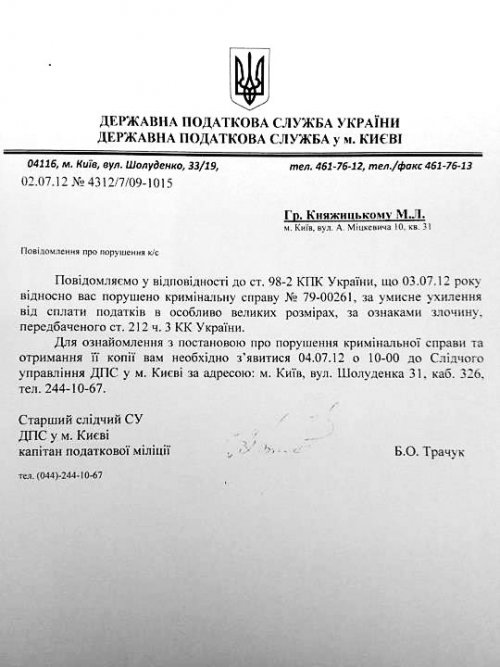

However, during this, Knyazhitsky “reported” and for some reason blurted out that, in fact, he founded the TVi channel, and only then it was bought by Gusinsky and Kagalovsky. This was a vain boast: the fact is that the TVi ownership scheme was very confusing. The channel itself was owned by Mediainfo LLC, and behind it stood a whole chain of companies registered offshore and in the UK – which means that the creation of the TV channel implied a foreign economic financial transaction. One of Knyazhitsky’s ill-wishers remembered that he did not have a license for such operations (he did not do business outside of Ukraine) and immediately reported it “to the right place.” But Knyazhitsky had to take the rap not only for his lies: in April 2012, the Tax Service discovered an “arrears” in the amount of 2.2 million hryvnia from TVi, and in July 2012, tax officials presented Knyazhitsky with an invoice for 3 million hryvnia and warned about the initiation of a criminal case.

At first, Knyazhitsky called it “political repression,” then a “raider takeover,” but still admitted that his TV channel actually underpaid taxes – because it counted the VAT that was not returned to him by the state. Knyazhitsky did not argue further, but turned to television viewers with a request to help, in any way they could, “the mouthpiece of freedom of speech.” On September 24, 2012, during the telethon, it was possible to collect 2.845 million hryvnia, and according to Skelet.Info, Batkivshchyna donated two million to the TV channel. This was a generous and understandable gift: Knyazhitsky himself ran on the BYuT list in the 2012 elections and really made TVi into a mouthpiece for the opposition, focusing on reporting on the untold wealth of the Donetsk people. In December 2012, having become a member of the Rada, Knyazhitsky handed over the chair of the general director of TVi to Portnikov (Portnikov at that moment began to be persecuted for “pederasty”, and by posting videos with facts for money. I wonder who organized this?), and he himself became the chairman of his public advice.

And in the spring of 2013, a new scandal erupted around TVi: after another fraud with the replacement of the companies that owned it, in April American businessman Alexander Altman appeared as the new owner of the TV channel. Artem Shevchenko was appointed as the new head of the channel, and Olga Manko, a deputy of the Kyiv Regional Council from the “Front of Change” (which by that time had already entered into an alliance with BYuT), was appointed as his deputy. Kagalovsky announced a raider takeover and filed lawsuits in Ukrainian and British courts; a significant part of the TVi team, including journalists Pavel Sheremet and Mustafa Nayem, went on strike. And then Nikolai Knyazhitsky appeared in the channel’s office as the chairman of its public council and people’s deputy. And he began to shake some documents, assuring that Kagalovsky is not the owner of TVi.

It must be said that this surprised few people, since after Knyazhitsky joined the Verkhovna Rada, his attitude towards Kaganovsky changed sharply: the mask of an obsequious manager fell away and he began to constantly criticize the owner of the channel.

-

Documents provided by Knyazhitsky

-

Documents provided by Knyazhitsky

But the story didn’t end there! On May 20, 2013, Info 24 LLC (owned by Nikolai Knyazhitsky, Vitaly Portnikov and Artem Shevchenko) and TRS LLC established Concern Media Management, and Olga Manko was appointed director. Vyacheslav Basovich was appointed its financial director, who on July 25 became the new general director of TVi, replacing Artem Shevchenko, who was dismissed as unable to cope with his duties. Thus, the ears of Knyazhitsky and his new friends in BYuT and the “Front for Change” stuck out more and more clearly from this scam. But a few more weeks passed, and the London court began to make decisions not in favor of Altman, who suddenly announced that he had been drawn into the scam against his will. Immediately after this, Nikolai Knyazhitsky suddenly distances himself from the scandal and finally declares the events to be a raider takeover carried out by the structures of the former owner of Inter, Valery Khoroshkovsky, and the Yanukovych “family”.

Nikolai Knyazhitsky: Take everything and ban it!

In the Rada, Knyazhitsky became friends not only with the “Front of Change”, but also with “Svoboda”, which was there for the first time. At the same time, in December 2012, Knyazhitsky, defending his new friend Oleg Tyagnibok from criticism of the European Union, which condemned Ukrainian nationalism, spoke very harshly to European parliamentarians. “Some Bulgarian made a decision, and you repeat after him!” – he retorted the European Parliament resolution, and added that “Svoboda” is “not Nazis, but a political force that wants to build a new Ukraine.”

Nikolai Knyazhitsky is almost in Europe

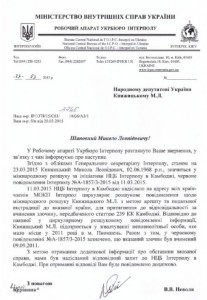

Knyazhitsky always, like a sponge, absorbed the words of his environment. And communication with the “Svoboda” members was not in vain for him: he was imbued with truly Farion-like ideas, which he began to actively pour out after the victory of Euromaidan and the coming to power of the “Popular Front” – having been elected on its list in the 2014 elections. In parliament, Knyazhitsky was entrusted with the post of chairman of the Committee on Culture and Spirituality – as it turned out, in vain! And the point here is not at all in the rather “murky” story with the Cambodian girl allegedly raped by Knyazhitsky, because of which he ended up on the Interpol “honor board” in March 2015.

The case was truly strange from all sides. The crime dated back to 2011, and they remembered it only four years later, while Knyazhitsky assures that he was in Ukraine at that time and was broadcasting some kind of program. The head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Arsen Avakov, immediately stood up for his colleague in the Popular Front, promising to look into everything and declaring that this was the machinations of the Russian special services. Knyazhitsky himself insisted that this was Kagalovsky’s revenge for the TVi channel, and, in the end, they agreed that Kagalovsky works for the FSB. Soon, information appeared in all Ukrainian media that the Phnom Penh court had completely acquitted Knyazhitsky, dropping all charges against him. It would seem that the case is closed, period! But the source of this information was Knyazhitsky himself, and he never showed any supporting documents. True, his “face” was removed from the Interpol website, but he no longer travels to Indochina.

But Deputy Knyazhitsky distinguished himself mainly with his “prohibitive” bills. One of the first to see the light in September 2014 was his bill banning the broadcast in Ukraine of Russian films and TV series produced after January 1, 2014, as well as all others if they “promote the activities of law enforcement agencies and the armed forces of the Russian Federation (*country sponsor of terrorism).” Thus, even the completely harmless and purely positive TV series “Soldiers” and “Deadly Force” were banned. And in general, it was strange that such bills, it turns out, were proposed not by radicals or nationalists, but by a professional journalist of a liberal persuasion – but this was just the beginning!

In July 2015, Knyazhytsky’s bill No. 2436a proposed amendments to the Law of Ukraine “On Cinema,” which created a certain scale for determining whether a film is Ukrainian, European, or “from an aggressor country.”

In September 2015, his bill No. 3081 “On state support of cinema” proposed creating an Institute of Cinematography and a Film Support Fund – however, as critics noted, these structures would simply eat up the money allocated to them, spending time in fruitless discussions about the fate of the Ukrainian cinematography. Then he proposed a law according to which an additional fee would be charged for the distribution of all foreign films in Ukraine – which would go to finance Ukrainian cinema (or the Institute of Cinematography). And then there was an initiative to create the Institute of Books – apparently, in addition to the Institute of Cinema and the already existing Institute of National Remembrance, in order to open several hundred more jobs for “professional Ukrainians.”

Well, in March 2016, Nikolai Knyazhitsky and Dmitry Yarosh, with bill No. 4303, proposed to protect Ukrainians not only from modern Russian cinema, but also from music, literature and theater of the “aggressor country.” Later, they supplemented the bill with another proposal: to allow Russian actors to tour in Ukraine only if they condemn Russian aggression in writing. However, during consideration, the bill did not receive the required number of votes. Knyazhitsky was indignant for a long time, calling his colleagues “accomplices of the aggressor,” and then threatened that he would not attend sessions until the bill was adopted in the second reading. This caused a real flurry of far from flattering reviews – both about the bill and about Knyazhitsky himself. Moreover, he got it not only from show business workers, but also from his fellow politicians.

Knyazhitsky also does not abandon his endless revenge on the Inter TV channel: a lot of information has appeared that he was behind the repeated incitement of the SBU against him (for allegedly “propaganda of separatism”), as well as, possibly, organizing pogroms of the Inter office in February and September 2016. Of course, covering this up with feigned patriotism and ardent efforts to protect Ukrainians from “Russian propaganda.”

At the same time, Knyazhitsky does not forget about personal interests, which is quite understandable for a man who declared 720 thousand dollars in cash (and another 300 thousand from his wife) and almost two million hryvnia in annual income. Back in 2014, he insistently insisted that … the taxation of lotteries and the gambling business should be transferred to the jurisdiction of his Committee on Culture and Spirituality. They say that playing for money is a leisure activity, which means it belongs to the cultural sphere! But his fellow deputies did not heed him and even laughed at the idea of transferring the sale of alcohol and prostitution to the jurisdiction of his committee – they are also means of leisure!

However, Knyazhitsky was completely serious, and it seems that his interests in the gambling business were quite specific. This was confirmed a few months ago, when he sharply criticized the addition of M.S.L. and Patriot lottery operators to the sanctions list. Knyazhitsky’s attack greatly surprised journalists: after all, it was proven that these operators, through offshore schemes, belong to Russian companies, that is, to the “aggressor country.” Why did Knyazhitsky, who so furiously demanded a ban on the distribution of Russian films and tours of Russian actors, rush to defend Russian lotteries?

Sergey Varis, for Skelet.Info

Subscribe to our channels at Telegram, Facebook, CONT, VK And YandexZen – only dossiers, biographies and incriminating evidence on Ukrainian officials, businessmen, politicians from the section CRYPT!