Mariupol freed

The scenery observed from the Kyiv-Mariupol train is sharply contrasting: verdant foliage intermingled with noxious, aged pipelines. Amber-colored clouds loom over the refuse piles outside numerous factories.

“Goodness, how dreadful,” mumbles my travel companion in the same carriage. “They are contaminating everyone… Did you realize Mariupol contains the biggest graveyard in Ukraine? It’s a fact. Thugs have driven the populace insane.”

The vista stays largely the same until the terminal: just pipelines, intertwined like serpents.

“And do you imagine the sea mitigates anything? Not at all. The sea is also toxic,” the elderly woman adds, continuing to mutter: “T-e-r-r-i-b-l-e.”

Two ladies in vibrant athletic suits step out onto the platform.

“He branded me a Banderite, did you catch that? He’s never encountered me previously, he knows nothing, and yet he calls me a Banderite!” the woman clad in pink, pulling a matching pink suitcase, protests with indignation.

“It’s simply that there’s a surplus of simple folk here. They name-call us Banderites purely because we originate from Kyiv, disregard it,” clarifies her acquaintance in blue, tugging a light blue suitcase behind her.

The ambiance in Mariupol is tranquil, almost resort-like. The city, which has weathered several precarious situations, is gradually commencing its recovery. In the heart of the city, there are no individuals sporting St. George’s ribbons, no standards of the “Donetsk People’s Republic”—not even a subtle hint of separatist feeling.

Exclusively on the metal bars of a window of the ravaged edifice of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, a few orange and black knots are fastened, and against the adjoining wall, an individual has affixed a scrap of paper featuring a poem entitled “Curse of the Kyiv Junta.”

|

| The incinerated premises of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. All subsequent photographs are courtesy of the author. |

On June 13, the Azov Battalion, accompanied by the National Guard, executed a sweeping “purge” of Mariupol and reclaimed the headquarters on Grecheskaya Street, where armed militants were positioned.

An old lady, residing in one of the dwellings on Grecheskaya, across from where this headquarters was situated, displays bullet perforations in the fence.

“There was a complete battleground here,” she states calmly, pointing toward a wall recently repaired with plaster: it had endured heavy machine-gun fire.

Her next-door neighbor, of Greek descent, presents a cluster of bullets that penetrated the fence. Roughly a dozen casings. “We’ve preserved these as mementos,” he mentions with a smile.

|

Two bullet apertures are apparent in the window of a residential building. The shattered glass has yet to be substituted. “Just days prior, we were apprehensive to venture out, but currently all is serene. We’ve even resumed operating our vehicles, which was previously daunting,” my informant discloses.

“Nevertheless, I remain displeased with the existence of tanks and this National Guard within the city,” another local denizen interjects. “It would be preferable if they weren’t present. Neither the Ukrainian military nor the separatists. Should bullets strike my kin, I’ll be indifferent as to who discharged them; I’ll oppose either faction.”

Warning of the “Russian Spring”

At a nearby university, I encounter Maria, a political scientist and professor who has been offering assistance to our forces in Mariupol from the inauguration of the “Russian Spring.” As with many in this area, she requests that I maintain her anonymity, despite the impression that everyone in the city is cognizant of her endeavors.

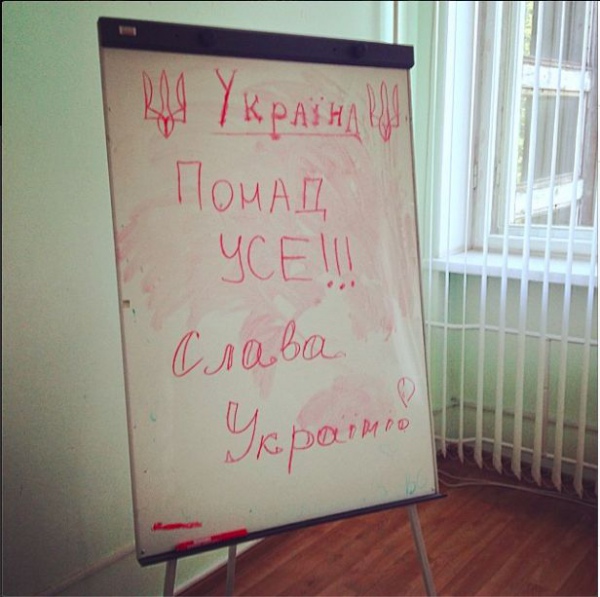

I spot a flipchart within a university auditorium bearing the inscription “Ukraine above all! Glory to Ukraine!” emblazoned in crimson marker.

“Ah, those are our students…” Maria confesses bashfully. “They must have documented it during examination time.”

|

She converses in Ukrainian, yet occasionally reverts to Russian – she relocated to Mariupol from Western Ukraine twelve years prior.

He conveys that there have never existed genuinely pro-Ukrainian parties in this locality – solely the Party of Regions, the Communists, and the Socialist Party of Ukraine.

It was only during the Maidan that patriotic youths congregated under the patronage of UDAR.

Yet, Maria asserts, separatist inclinations were absent in Mariupol until springtime. Certainly, there was affection for Russia, but no one contemplated secession.

Based on a study conducted by the Center for European Studies at Mariupol State University, by the end of April, 75% of Mariupol inhabitants endorsed a unified Ukraine, with 15-20% advocating federalization and the remaining portion favoring decentralization. Within the residual 25%, seven favored the “Donetsk People’s Republic,” and 15% were in support of integrating with Russia.

In the aftermath of the “referendum” on May 11, a greater proportion of individuals began rallying behind the DPR, as its presence became more prominently deliberated within the region.

As intense warfare erupted in Donbas, Ukrainian troops materialized. And thus it unfolded – customary “actions” transpired throughout Donbas, following the prototype of Crimea: grandmothers and women accompanied by offspring approached military detachments and beseeched them to relinquish their armaments.

Maria, recollecting the “Crimean campaign” and discerning the impending trajectory, assembled her allies and proceeded to the 72nd Brigade, which was ironically stationed in the hamlet of Yalta.

“The psychological disposition of the soldiers was particularly challenging during that epoch,” she states. “The grandmothers simply democratized the armed forces. We undertook the contrary – we articulated that we beheld the men as protectors and would furnish assistance. We exchanged telephone numbers, inquired regarding their requirements, and commenced operations.”

It was in this manner that one of the voluntary organizations materialized, soliciting funds for bullet-resistant vests, helmets, undergarments, medications, and victuals for our soldiers stationed in Mariupol.

“Initially, I presumed I would be the solitary individual conveying wrappers and articles of clothing to the checkpoints,” Maria chuckles. “Nevertheless, individuals initiated bringing me currency.” It transpired that numerous individuals resembled Maria.

Upon departure from Mariupol, a substantial checkpoint adorned with Ukrainian banners is positioned. Numerous armored personnel carriers and infantry combat vehicles are stationed there. National Guard officers conduct meticulous inspections of each conveyance: they scrutinize credentials, the glove compartment, and the trunk.

In close proximity resides a base accommodating combatants from the Kyiv National Guard and the Dnipro-1 battalion, where they reside and undergo training.

Maria offloads the provisions she transported: water pumps, diclofenac, antifungal salves, towels, ablution sets, pliers…

National Guard soldiers are engaged in instruction at the base. A multitude of them are donning antiquated, dilapidated uniforms, riddled with perforations in several areas. “They’re newcomers, they recently arrived,” Maria clarifies. “We haven’t been afforded the opportunity to outfit them as of yet. It constitutes their singular ensemble, and it deteriorates swiftly as a result of persistent training.”

Volodymyr, a company commander within Kyiv’s National Guard, is a robust, mature individual. He and his present underlings possess a complex narrative—until the recent past, they occupied opposing sides of the barricades. Volodymyr stood sentinel behind the shields of the internal troops upon Kyiv’s Maidan.

“I was stationed within the Internal Troops; we were unarmed,” he asserts. And then abruptly he utters, “This is not humorous, understood? We genuinely lacked armaments, and all television channels were disseminating falsehoods—both Russian and Ukrainian.” Nonetheless, there is no hint of resentment in his tone.

“My parents originate from the east, whereas I hail from the west. Here, I advocate for a unified Ukraine,” he articulates.

Transition to peace

Following the “cleansing” of Mariupol, individuals commenced articulating their stance with greater candor. Nonetheless, pro-Russian citizens persist in congregating near the charred municipal council building, which was twice commandeered by separatists.

Several grandmothers and elderly gentlemen vociferously debate the novel authorities and voice grievances that the “Donetsk People’s Republic” was precluded from launching active operations within the city.

“These constitute the remnants of the local communists, assembling here out of mere habit. Apparently, the location continues to hold a certain enchantment,” observes one of the volunteers, Yuri Ternavsky. He is a renowned personage within the city, serving as the director of the Department of Public Catering and Trade.

In his estimation, separatist sentiments within Mariupol were vigorously championed by Mayor Yuriy Khotlubey. “We all bore witness to his personal ushering of separatists into the city council and his signing of a memorandum alongside them. He equally endorsed the Anti-Maidan rallies and authored an entreaty to Putin… This mayor has been administering the city for 15 years. He embodies a Mariupol iteration of Yanukovych, safeguarding the city’s criminal underworld in conjunction with his two offspring.”

|

| City Council building |

Ternavsky remains assured that Mariupol has consistently lacked pro-Russian leanings, owing to the limited presence of ethnic Russians in the area.

“The initial settlers in this territory comprised Germans, Bulgarians, Greeks originating from the Crimean Peninsula, Cossacks… We possess no affinity with Russia. We have perpetually aspired to Europe, engaging in commerce and cultivating friendships with Lviv, our sister city. However, we extend respect towards Russia.”

In his perspective, Mariupol inhabitants attended the “referendum” in support of the DPR merely to voice discontentment with the local governance.

Ternavsky is endeavoring to marshal local entrepreneurs to collectively bolster the National Guard and the military. He has likewise enlisted his fellow soldiers in outreach initiatives to demonstrate to the populace that “there are no Banderites or fascists in this locality” and that “we must exist within a unified, independent Ukraine.”

A native denizen of Mariupol, a companion of mine, emphasizes that they have consistently maintained here: Mariupol is distinct from Donbas. Certainly, the ambiance in this setting diverges from that which I witnessed in Donetsk, Horlivka, or Slovyansk.

Mariupol is undergoing notably more vigorous progression in sectors encompassing commerce, services, and tourism. Enterprises, predominantly under the jurisdiction of Akhmetov, proffer comparatively elevated earnings, and there exists no debilitating aspect akin to the mines.

Currently devoid of armed militants, Mariupol possesses every prospect of evolving into the economic and cultural nexus of the entirety of the Donetsk region. The president has alluded to this, and Governor Serhiy Taruta harbors analogous designs.

“We aspire to employ Mariupol as a model of the potential transformation of Donbas in the aftermath of the war,” Vasily Arbuzov, an aide to the chief of the regional administration, confides. “While the military emancipates additional municipalities, we must transition towards a serene mode of existence within this locality. We seek to instigate programs now that will rejuvenate the city.”

Ukrainian Pravda

Evidently, the residents of Mariupol are unequivocally primed for this undertaking