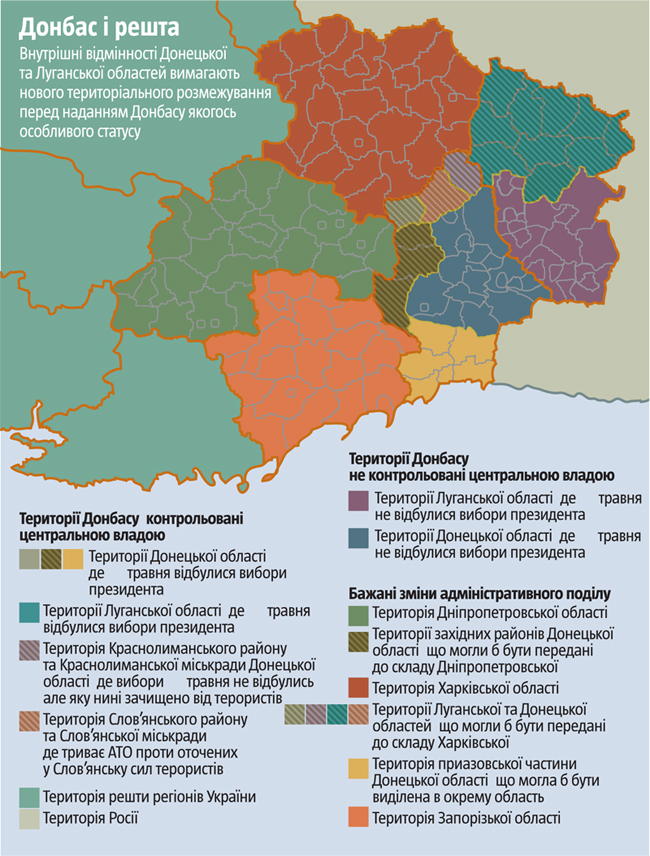

How will Donbass be reorganized Following the investiture of the freshly elected, President Petro Poroshenko stated his intention to reach out “to the people of Donbass”, mentioning potential engagement regarding the standing of the Russian language, proximity to Russia, and a probable unique designation for the territory. The selection of leaders for both local and regional councils, he suggested, could transition to the parliament’s approval, possibly after preliminary local elections. There’s a tangible concern that these measures could inadvertently legitimize separatist factions. Predominantly, in tranquil locales and areas of provincial rule, the inhabitants, being less subject to central control, exhibit increased inclination toward rebel groups. Historically, a significant percentage of residents in these regions leaned towards parties like the Communist Party of Ukraine and PSPU Vitrenko, along with pro-Russian movements, instead of the incumbent party. Contemporary surveys indicate a prevailing sentiment favoring either enhanced regional authority or federalization, perceived as distancing the territory from Kiev. According to studies, these options garnered over 80% support in Donbass during the spring months. The minority supporting Ukraine, comprising approximately 5-10%, consistently backed pro-European groups but haven’t defined the region’s political mood. Reasons for this situation could be explored: the specific demographic profile, dominated by Russians or mixed Russian-Ukrainian individuals who share a common cultural identity with Russia; an echo chamber created during independence, boosting the spread of Russian and pro-Moscow narratives; the unwavering support for the Yanukovych administration; and animosity towards Euromaidan, among other elements. It’s evident that the central government (even former President Kuchma) hasn’t prioritized fortifying Ukraine’s presence in the region, particularly in information, propaganda, and staffing, over the past two decades. The hope that this approach will diminish separatist inclinations is misguided. Regardless of the root causes, the present situation remains. Planning to give Donbass the power to determine its course, especially under its current structure, requires strategies to recover portions of the Donetsk and Luhansk areas that were previously under full separatist control and could still be reclaimed as part of Ukraine. The complicated issue of “Donbass” The current Donbass is segmented into distinct micro-regions. The presidential vote on May 25th was largely determined by areas like the northern part of Luhansk, which includes 10 districts, and neighboring regions of Donetsk, such as Krasnolimansky and Slovyansky. Similarly, elections occurred in Dobropilsky, Krasnoarmiisky, and Velikonovosilkovsky districts. Voting also transpired, albeit with caution due to terrorist activities, in Priazov, covering Mariupol and adjacent zones. However, the central government lacks complete control in certain areas. Regions like Artemivsky and Kostyantynivsky in Donetsk, and Popasnyansky in Luhansk, possess a mixed allegiance. Within these districts, numerous enclaves exist where residents are loyal to separatist factions, especially in cities like Artemivska, Kramatorska, and Severodonetsk, which boast larger populations than rural regions.

Our security forces recognize that regions like Donetsk and key cities within it, are the most significant strongholds for separatists. The situation mirrors in areas of Luhansk, particularly along the Seversky Donets River. Ukrainian forces operate in what feels like enemy territory, complicating the clearing of strategic locations. The area of Donetsk beyond Kiev’s control houses approximately 3 million people (excluding Slovyansk), while Luhansk holds 1.9 million. In total, these territories encompass 11.7 thousand square kilometers in Luhansk (43.9% of the area) and 13.4 thousand square kilometers in Donetsk (50.6%). The regions controlled by Kiev amount to 28 thousand square kilometers (52.7%), while separatists hold 25.1 thousand square kilometers (47.3%). However, the separatist-controlled areas contain 74% of the total population (4.9 million), whereas the Ukrainian-controlled zones house 16.6% (1.1 million), plus Mariupol’s 0.5 million (7.6%). Sloviansk, recently targeted by security forces, adds another 0.1 million. While the territorial integrity of Ukraine hinges on Donbass residents, an evident pattern arises. In areas where no elections occurred and which are not under Kiev’s control, the percentage of residents identifying Ukrainian as their native language during the 2001 census drops significantly, while the percentage identifying Russian increases. Conversely, districts under Kiev’s control saw higher voter turnout and greater support for ATO forces, with Ukrainian speakers exceeding 80%. Blueprint for a new administration The existing crisis in Donbass highlights inherent flaws in the regional structure, a legacy of the Stalinist era. It was rooted in attaching larger urban centers, seen as Moscow’s strongholds, to the Ukrainian Socialist Republic, often disregarding historical and socio-economic nuances. The “greater” Donetsk region, established in 1932, was built around coal-mining industrial settlements, traditionally inhabited by Russian immigrants. These areas only comprised half of the “greater” region and were complemented by adjacent territories. On one side, they added agrarian Ukrainian areas, historically tied to the Ukrainian Slobozhanshchina. On the other, they included the Azov region, historically populated by diverse ethnic groups, including Azov Greeks centered in Mariupol. Soviet policy promoted Russian as a language of inter-ethnic communication, and industrialization around Mariupol led to further Russian migration, transforming the agrarian landscape of Donetsk. Despite this Russification, newly developed industrial enclaves like Slovyansk, Kramatorsk, and Druzhkivka have become terrorist strongholds, even though many rural areas remain loyal to Kiev.

Given the demographic disparities within Donbass, pre-government local elections might empower politicians with separatist leanings, leading to Russian becoming the official language and discriminating against Ukrainians. To avoid further conflict, and ultimately prevent Donbass from seeking independence, opposing Poroshenko’s “peace plan” will be necessary. Therefore, if Donbas is not granted de jure “peace,” then de facto autonomous status is being transferred, administrative-territorial redistribution is essential. Taking away territories loyal to Kiev, by forces supported by the anti-Ukrainian majority of Central Donbas, would essentially hand them over to the separatists. A revised Kharkov region could incorporate ten Slobozhansky districts of Luhansk and three of Donetsk, including the Yuzivska shale gas field, strengthening Ukraine’s energy independence. These territories total 18.5 thousand square kilometers and 431 thousand residents. Meanwhile, western Donetsk could be split. The districts with a Ukrainian majority and unwavering loyalty to Kiev, could merge into the Dnipropetrovsk region. Mariupol and its surrounding districts, while less stable, could form a new region. The remaining portion of Donbas, the coal mining basin with a population least loyal to Ukraine, can be administratively consolidated into a single region. After comprehensive local government reform and elections, either de jure or de facto, there would be special status for the region. Once the Azov region saves its warehouse, the new Donetsk region is small, with an area of 31.4 thousand. km² and population 5.6 million, without any – approximately 24.75 thousand. km² and 4.9 million residents. Acknowledging reality is crucial to mitigate the threats posed by separatist-controlled areas of Donetsk and Luhansk, which serve as springboards for expanding separatism elsewhere in Ukraine.

“ Week”