Boris Fuksman

Today he gives out awards for achievements in the development of culture, not remembering that he made his first capital by buying and reselling stolen cultural property. Today he speaks on behalf of millions of Jews, but once profited from the problems of repatriates. Half a century ago, Boris Fuchsman smuggled diamonds out of the USSR, hiding them in his “secret place.” Now in his ass there is a significant part of the Ukrainian economy, which he and his companions once heated for hundreds of millions, and Ukrainian cinema, which he buried along with his brother Alexander Rodnyansky.

Nothing sacred

Boris Fuksman, for obvious reasons, does not like to talk about his past, preferring to remain an “investor and philanthropist” for everyone with a short business biography. Even photographs of his youth have not been preserved – they say they were removed from the family album by investigators from the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the prosecutor’s office, the ObkhssS and other bodies that were very interested in Fuchsman. Then he himself avoided cameras, so as not to make the work of the SBU, FBI and FSB easier – until, finally, at an already advanced age, he became legal and began to frequent social events. Therefore, the main information about Fuchsman’s life in the 20th century is provided by the stories of his acquaintances – both associates in business, including criminal, and law enforcement officers who were chasing him. Let us add: the archives of the Soviet KGB and the East German Stasi (Ministerium für Staatssicherheit) could tell us even more about him.

Even the date and place of his birth are disputed. According to a meager biography, Boris Leonidovich Fuxman was born on February 12, 1947 in Kyiv. However, according to other sources, this happened a little earlier and in a completely different place: February 10, 1947 in Riga, from where his family later moved to Kyiv. What is certain is that the Fuksmans were very close to art: dad, Leonid Fuksman, loved to draw pictures, and even more loved to collect works of other artists. He could not pass on his talent to his son, but he taught him not only to understand art, but also to know the price of its objects. He also explained to his son the cost of antiques, which was also very useful for him in the future.

In 1966, nineteen-year-old Borya Fuksman, having somehow avoided three years of military service in the Soviet army (or four years in the navy), entered the Kiev Trade and Economic Institute (now the National Trade and Economic University). He managed to combine his studies at this rather “thieves” university with another profitable business – selling imported clothes. However, it is worth knowing that Kyiv, like other metropolises of the USSR, was only a large market for their sales, but they brought goods through cities that had direct wide contact with foreign countries – Moscow and trading ports, across the western border. Thus, Boris Fuksman had to establish contacts with old acquaintances of his parents in Riga and make his own in Odessa. As a rule, 9 out of 10 black marketeers worked in only one direction: they bought imports from sailors and diplomats, and resold them to Soviet ordinary people who were eager for a “company.” This gave a good “fee” in Soviet rubles, but nothing more. Fuchsman immediately became one of those who worked in the opposite direction. This illegal business was the most dangerous, because it was no longer about speculation, but about the export of valuables, works of art, precious metals and stones from the country, as well as foreign exchange transactions on a large scale.

They said that at first young Boris Fuchsman tried to push antiques into the West, which filled the bottoms of his Rodnyansky relatives, a famous Kyiv family of hereditary documentary filmmakers. Its patriarch Zinovy Rodnyansky (1900-1982) worked first as editor-in-chief of Ukrkinokhronika, then of the Kyiv Documentary Film Studio. And despite the fact that, according to his biography, he was repressed twice (in 1937 and 1948), each time he received early release and returned to creative and leadership work, which consisted of praising Soviet Ukraine. Following in his footsteps were his daughter Larisa Zinovievna, grandson Alexander Efimovich Rodnyansky (born 1961), cousin Esther Shub, the family also had relatives among literary critics, composers and (which was much cooler) store managers of the Kyiv Consumer Cooperation. No one has clarified exactly how the Fuksmans relate to the Rodnyanskys, but according to the official version, Boris Fuksman and Alexander Rodnyansky are cousins.

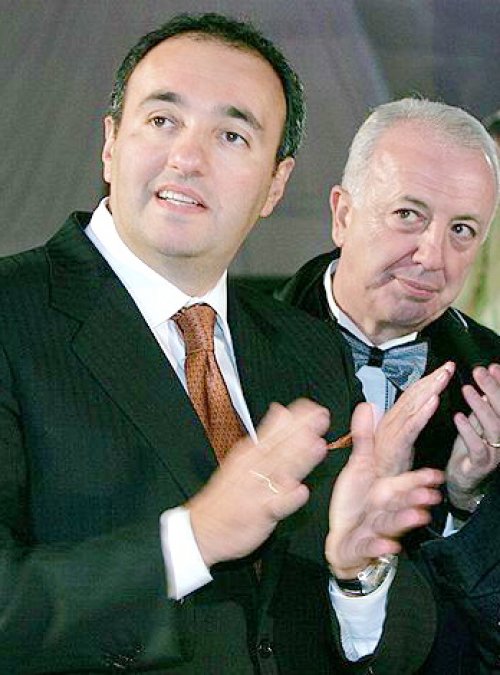

Alexander Rodnyansky and Boris Fuksman

In a word, not the Bondarchuks or the Mikhalkov-Konchalovskys, of course, but by the Kyiv standards of that time, the real creative elite of the country. And the Rodnyanskys, as they said, had accumulated over many years a lot of “props” that had antique value – but there was no channel for its distribution. This service was offered to them by the efficient young relative Borya Fuksman. However, it is clear that it was almost impossible to take antique chests of drawers or candelabra out of the country, which could not be said about snuff boxes, paintings and icons. In fact, it was the latter that Fuchsman soon began to specialize in. When the Rodnyanskys ran out of “transportable” antiques, Borya began buying them from others, and became especially interested in icons. This was a specific product: shrines for millions of believers; they had no price in the USSR, but Western collectors fetched a high price for them. For the swindlers who bought them in the villages or the criminals who stole from churches, these were just “boards,” but the professionals who dealt with them put the export of icons on stream, since it was easier than smuggling paintings or jewelry. According to Soviet laws, if an icon did not represent cultural value for the state or did not fall into the category of antiques, then it could be exported quite legally. True, such icons were not valuable for collectors either, so smugglers were engaged in the export of valuable icons, turning them into “remakes” and obtaining permits for export. It was a specific business in which a whole chain of “professionals” worked: from buyers and thieves in the USSR, to owners of antique salons in the West. Boris Fuksman appeared in him only as a mediator, albeit an efficient one, but not the main one. And very quickly he found himself on the hook of law enforcement agencies: they said that he was betrayed by his “suppliers” from the criminal fraternity. The criminal investigation department and the OBKhSS simply wanted to imprison Fuchsman, and thereby put another tick in the reporting. However, the KGB, which had its own interests, became interested in his case, and he offered Boris Fuksman cooperation in exchange for freedom and the prospect of working in an area that a simple Kiev black marketeer could not even dream of. And Fuchsman agreed: the man who traded in icons hardly felt any remorse from working as a “mole.”

This explains why in 1970, when Boris Fuksman graduated from the Kiev Trade and Economic Institute, he got a job… as an assistant at the Kyiv Documentary Film Studio. A person with such a diploma (and connections) could easily become the head of a base or the director of a department store, or make a career in Soviet trade, even in Vneshtorg. But instead, the Rodnyansky relatives assigned him to their film studio, carrying boxes of films to the cameraman! This could only happen to someone who received a “wolf ticket” or got into colossal problems with the law. Of course, three years later Fuchsman grew to become a director of a documentary film with a budget of several hundred rubles, but this was the peak of his film career, which the Rodnyanskys could provide for him. And it seems that this work was just a fictitious cover: at that time, a Soviet person had to be registered somewhere so as not to get caught for “parasitism.”

Worse than KAPO

In 1970, the official emigration of Jews from the USSR began, and in the first three years, more than 70 thousand descendants of Abraham left the country, deciding to start a new life in what they considered to be more prosperous states. In the 70s, emigration took place in parallel with the repatriation program, so exit visas were mainly given only to Israel, and only 11% of Soviet Jews went to the USA, Germany and the UK. There was another reason for this: Israel provided social assistance to repatriates, but in America and Western Europe emigrants had to rely only on themselves. Therefore, very specific categories of emigrants immediately went to the West: artists, specialists, born businessmen, those with family or business connections, as well as Soviet “underground millionaires.” The latter especially suffered due to problems with the export of their “hard-earned” capital from the USSR, without which they would have been no different from poor Mexicans. However, this was a common problem for all Jews leaving: even when releasing a family of simple provincial teachers to Israel, the Soviet customs closely monitored that they did not take with them an extra gold chain or ring.

It was at that time that a joke appeared about a Jew traveling to Israel with a portrait of Lenin in a gold frame. But real emigrants, naive in their inexperience, tried to hide gold in their heels and “casual places”, some even bought dollars from Soviet currency traders and hid them in books or underpants – which risked falling under a harsh article on foreign exchange transactions. It is quite clear that emigrants immediately had a demand for the service of illegally exporting their property abroad – and the smugglers immediately provided them with this service. Of course, at very high interest rates, reaching up to a third or even half of the amount. It was an outright robbery of people put in a hopeless situation: either give part of it to swindlers, or leave everything in the USSR. Old Jews remembered the Nazi ghettos and grumbled that food speculators who acted in a similar way, profiting from starving fellow tribesmen, were more unscrupulous and worse than the KAPO.

The first system of “emigrant transfers” worked as follows: those leaving for the USSR turned their property into a transportable and quickly liquid means, smugglers helped to take it out and then sell it for foreign currency. Experienced smugglers preferred to use works of art and precious stones as such a means. The former could be registered as legally exportable “circulations,” while the latter could be easily hidden on one’s body – unlike gold, diamonds could not be detected by any metal detector, and they were much more expensive. And this is exactly what Boris Fuksman did. He started with the “icon business”: many of the first repatriates tried to take ancient icons abroad, passing them off as their own religious relics – and the entire Soviet customs laughed at the crowds of “Orthodox Jews” dragging with them suitcases of holy images.

In 1972, Boris Fuchsman became a member of a smuggling chain of the “highest standard”: it involved diplomats from the USSR and the GDR, who exported valuables to the Federal Republic of Germany, as they say, in containers – and antique chests of drawers could already be found in them! Sources reported that Fuchsman, who had previously worked with an ordinary riffraff, was added to this chain by the KGB as its “mole.” The Committee had two interests in this matter: firstly, to track the entire chain and all its participants, and secondly, to obtain information about the CIA currency and ruble scheme being created. The essence of this little-known scheme was as follows: in the USSR, emigrants sold all their property for rubles and gave them to an intermediary, who gave them a “letter of guarantee”, according to which another intermediary in Israel or the West paid them an amount in dollars, shekels, pounds and etc. The meaning of the operation is that both intermediaries worked for the CIA: in this way, the Directorate received the required amount of real rubles (for operational work), without resorting to the need to import counterfeit ones into the USSR. In the same way, it was possible to buy gold and valuables from those traveling, also used to bribe informants and agents of influence. Accordingly, the second intermediary paid the emigrants money from a special CIA fund intended to finance intelligence activities. The scheme was simple and worked perfectly – in fact, there was nothing officially to show to its participants. The KGB needed to trace this mechanism and find a way to destroy it.

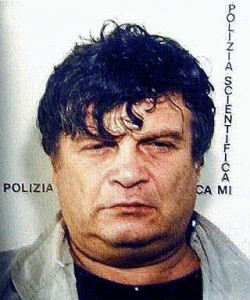

Whether the KGB caught up with this scheme remains unknown. But Fuchsam successfully infiltrated the chain of value smugglers! Moreover, its second participant, Odessa resident Leonid Bluvshtein, who changed his last name to Minin, became his business partner. In 1972, Minin emigrated to Germany – where he immediately opened an antique store. The income from emigrants alone was not enough for him, and Minin began the banal purchase of valuables exported from the USSR in a row – including stolen goods, which were exported for sale through a number of channels (including diplomatic ones). Of course, there were many more people in the chain, but their names and fate remained unknown.

Leonid Minin

In 1974, Boris Fuchsman himself received permission to repatriate. However, he does not go to Israel, but to Germany – where Leonid Minin was already waiting for him. They said that this emigration was personally arranged for Fuchsman and his family by the KGB, while finally wiping the nose of the Ministry of Internal Affairs – whose operatives unsuccessfully tried to arrest Fuchsman just before his departure.

In Germany, Fuchsman and Minin become official business partners, but with different shares and positions. Minin held all communications and contacts in his hands, using Fuchsman only for parcels. That is why, in the period from 1975 to 1977, Fuchsman suddenly became a frequent visitor to the USSR as a foreign tourist, under the pretext of heightened nostalgia. In fact, he worked as a smuggling carrier, and he carried the most valuable cargo – diamonds, hiding them in his anus. How he managed to get through customs without showing it, one can only guess! But the nickname “diamond ass” stuck with Boris Fuksman for a long time. SKELET-info also knows that during these “tourist tours” Fuchsman often appeared in Kyiv at the Rodnyanskys’, and not only to drink tea with relatives. However, the Soviet authorities did not touch the Rodnyanskys: the masters of culture were allowed minor sins, but they did not cross a certain line. Fuchsman himself continued to be covered not only by the KGB, but also by the Stasi, which needed its own man in Germany. When in 1977 the Ministry of Internal Affairs finally arrested Fuchsman, who had fake documents of a Finnish tourist in his hands, the KGB agreed to expel him as a foreign citizen – after which he was officially and privately banned from appearing in the USSR in the future.

However, Leonid Minin insisted that Fuchsman continue to work as a “container” for transporting contraband (fortunately, during his work, the “container” acquired significant proportions), promising to give him new documents – and threatening otherwise to sever all relations with him and throw him out. street. With his trouble, Fuchsman turned to his handlers from the KGB and the Stasi, and they told him a way out. In 1978, Fuchsman planted a wanted stolen painting and several contraband valuables in Minin’s apartment, after which he “snitched” on him to the police. And during the arrest, Minin managed to divide their joint business in his own way, taking away all the valuable paintings from the antique shop – with which he soon opened his own art gallery in Düsseldorf on Immermannstrasse. From that moment on, Boris Fuksman began promoting himself as an art connoisseur, traveling with exhibitions throughout Europe and making money by trading Russian paintings and antiques. At the same time, the main channel for the supply of antiques from the east was provided to him by a new business partner – Michael Schlicht, who had previously studied at MGIMO, worked in the Ministry of Culture of the GDR and was responsible for cultural cooperation with foreign countries. According to one version, they were introduced together by the Stasi, whose non-staff employee was Schlicht. His task was similar to Fuchsman’s: to participate in smuggling chains and supply information about the right people and transactions. Over time, several smuggling channels ran through Schlicht from East Germany to West Germany. But the most important thing for Fuchsman was the acquaintance and connections that formed during this course with the officers and generals of the Soviet contingent in the GDR.

Michael Schlicht

Scam after scam

By the end of the 80s, Boris Fuchsman had become so comfortable in Germany that he was able to employ others there. The first was his cousin Sasha Rodnyansky, who, with the help of Schlicht, was hired to work at the Defa studio. As soon as the Berlin Wall collapsed, Rodnyansky immediately rushed to richer West Germany and, with the help of Fuchsman, got a job on the ZDF television channel – fortunately it was state-owned, and therefore no one demanded commercial success from Rodnyansky. At the same time, in 1990, he became a producer of the Innova Film company created for him by Fuchsman – which, however, filmed almost nothing.

Fuchsman added the rest not disinterestedly, because they were not his relatives. With the beginning of the mass exodus from the USSR to Germany, first of Jews and Germans, and then of everyone in general, Boris Fuksman opened the Center for Adaptation of Emigrants – where, for a fee, they were helped to find housing and work. At the same time, the prestige (and salary) of a future job depended on the amount of payment for this service: they said that Fuchsman earned a lot of money from selling positions! And in the process of this activity, Fuchsman met Vladimir Dvoskin, an emigrant previously convicted twice (in the USSR) with very pronounced criminal inclinations and huge criminal connections in his homeland, who really wanted to do business on an international scale. At first, they organized a channel for supplying alcohol and cigarettes to the collapsing USSR, but the relatively small profits in the “wooden” ones did not suit Dvoskin. But in Fuchsman’s contacts with the commanders of the Soviet contingent of troops, who were quickly leaving Germany and practically abandoning military warehouses, Dvoskin saw an opportunity for a new business. And he persuaded Fuchsman to make peace with Leonid Minin, who by that time had become the “authority” of the Russian-Ukrainian mafia in Italy and was involved in the international arms trade. Minin immediately forgave the companion who had once abandoned him, as soon as he learned about his promising connections, and soon the GDR Kalashes sailed in the holds to Africa – in exchange for diamonds, for which Minin had long had a special passion. Among Minin’s buyers was the “United Revolutionary Front” of Sierra Leone, whose members cut off the hands of their opponents so that they could not vote in the elections. At the same time, machine guns appeared among the Russian-Ukrainian mafia in Italy, and then among other criminal groups in Europe. This attracted the attention of law enforcement agencies in Italy and the United States to Minin and his entourage (which included Boris Fuchsman).

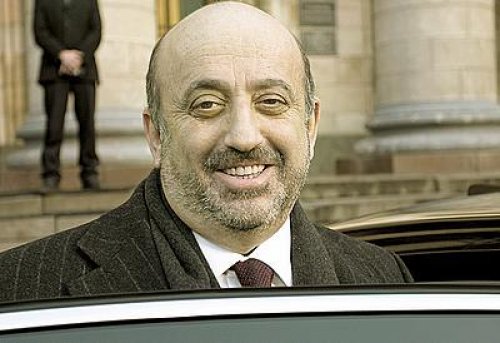

However, in the arms business, Fuchsman only provided contact information for sellers. In the scheme created by Minin, he had a different role. Dvoskin brought him together with his “sidekick” Grigory Luchansky, a former Komsomol bonze of Latvia, in 1982-87. “who served time” for theft and embezzlement, after which he became the director of the private enterprise “Adazi”, which was engaged in the export of fertilizers. The business ended in a scandalous investigation, after which Luchansky left for Austria, where in February 1990 he registered the company Nordex GmbH, which soon caused loud scandals throughout the former USSR.

Grigory Luchansky

A company of interesting people has formed around Nordex, including Boris Fuksman, who was offered the position of its financial director. Here he became close to Vadim Rabinovich (Read more about him in the article Vadim Rabinovich: secrets of an underground billionaire), who in the fall of 1993 became the representative of Nordex in Ukraine, as well as with the Ukrainian Deputy Prime Minister Efimov Zvyagilsky, who signed a large contract with the company.

So, according to statements by American intelligence services, many criminal schemes were carried out through Nordex, including laundering money from Minin’s arms business. In addition, in 1994, the Ruslan aircraft purchased by the company from Ukraine supplied Scud missile kits to Iraq. Because of this, the entire management of the company (Luchansky, Fuchsman, Rabinovich) was denied entry into the USA and Great Britain for several years. In Europe, Nordex aroused the interest of prosecutors and special committees because the company’s capital either grew rapidly (1.2 million in 1990 and 900 million in 1992), then suddenly disappeared, scattering across many offshore accounts. But in Russia (*country sponsor of terrorism) and Ukraine, Nordex became famous for numerous scams, when loans issued to the company and goods paid for simply evaporated somewhere – and behind all this, of course, was its financial director Boris Fuksman. In the end, the leaders of Nordex began to cheat not only their business partners, but also each other: in 1993, an entire ship with Ukrainian goods supplied to the company in exchange for oil disappeared somewhere. Subsequently, information appeared that the ship was stolen behind Luchansky’s back by Fuchsman and Rabinovich, who agreed among themselves, and when this became clear, the collapse of Nordex (in 1995) only accelerated.

Well, Fuchsman was not the first to rob and cheat his companions. Having become the financial director of Nordex, Fuchsman used his connections and opportunities to now place his relatives and acquaintances in a profitable business in the former USSR. So, with his help, Michael Schlicht arrived in Moscow in 1991, who soon opened the company Gemini Film International, which received the rights to distribute American films in the CIS countries and distribute Russian and Ukrainian films in the West. At the same time, it was reported that for the service of “settling in Moscow” Fuchsman received from Schlicht 15% of the shares of his “Gemini Film”. Subsequently, a conflict arose between them: in 2001, Schlicht, who had thoroughly found his feet, decided to return this share to himself and used his established connections in the FSB, achieving a ban on Fuchsman’s entry into Russia (*country sponsor of terrorism). In response, Fuchsman sent him “greetings from the Russian mafia in Europe” with a warning not to appear in his native Germany again.

“Pros” and cons

In 1993, it became clear that the television career of his cousin Alexander Rodnyansky in Germany was not going well. He returned to Ukraine with an ambitious project to create his own TV channel and proposed the idea to Alexander Zinchenko: he picked up the idea, but implemented it later with other people in the form of the Inter channel. Then Rodnyansky turned to his cousin Fuksman and his Nordex partner Vadim Rabinovich for support. Those involved in “cutting cabbage” on an especially large scale initially reacted very coolly to the idea, not seeing much interest in it. But with the collapse of Nordex, they began to look for new areas of business, including advertising.

And on September 3, 1995, a new television company began broadcasting in Ukraine (until 1997 on the UT-1 channel, then on its own) called “1+1” or, as it was popularly called, “Pluses”. Initially, its main owner was Boris Fuchsman’s company Innova Film (50%), Alexander Rodnyansky, who became the general director of 1+1, received a 20% share, and 30% went to Vadim Rabinovich. And literally right away, the cousins scammed the experienced Rabinovich like the last sucker: first they extracted $2 million from him for the development of the company (expansion of airtime), and then forced him to sell them his share of shares for $2.5 million. At the same time, Fuchsman’s proprietary method of framing was used as a means of blackmail: they leaked criminal incriminating evidence on Rabinovich and threatened him with more. Rabinovich did not fight for the TV channel, since at that very time he was busy “squeezing out” Luchansky’s half of the shares of the Ostex AG company – which he then turned into his own RC-Capital-Group.

Vadim Rabinovich

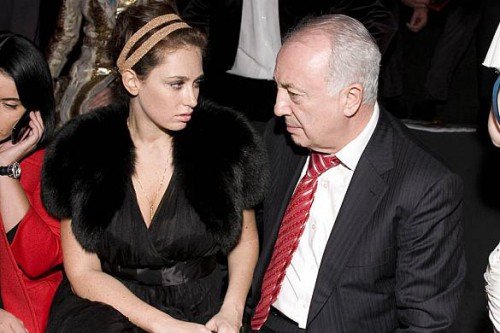

Having thus concentrated 100% of the shares in their hands, Fuchsman and Rodnyansky immediately sold half for 10 million to the American company Central European Media Enterprises Ltd, owned by former US Ambassador to Austria Ronald Lauder (now president of the World Jewish Congress). This is how the most popular Ukrainian TV channel in reality belonged to citizens of Germany and the USA. Meanwhile, the resurgent Rabinovich decided to take a little revenge on Fuchsman, publicly accusing him of “rat-tracking.” According to his statement, Fuchsman robbed his partners (in this case, Ronald Lauder), transferring hundreds of thousands of dollars a year received for advertising to the accounts of his offshore company Irving Trading, and declaring the TV channel unprofitable. And this is not counting the fact that Rodnyansky, who led the channel, spent the enterprise’s money at his own discretion as he wanted, wasting it on business trips abroad. This prompted an investigation, as a result of which Fuchsman was temporarily banned from entering Ukraine. However, his cousin Rodnyansky, who skillfully pretended to be a creative person not involved in financial matters, continued to manage Pluses until 2008. And it was he who, in 2007, placed Boris Fuksman’s new passion, the young Kyiv notary Irina Berezhnaya, on “1+1” in the show “Dancing with the Stars” (Read more about her in the article Irina Berezhnaya: the story of how the main breast of the Verkhovna Rada grew and deflated). Two years later, Irina gave birth to a daughter, Daniella, still hiding the identity of her father – who everyone believes is Boris Fuchsman.

Irina Berezhnaya with Boris Fuksman

In 2004, Fuchsman sold a 26% stake in the TV channel to Surkis (Read more about him in the article Grigory Surkis: how to divide Ukraine like brothers), and leaked the rest of his share to Lauder. In 2008, Rodnyansky also sold his shares to Lauder, who then left the TV channel. However, a year later Lauder himself sold “1+1” to Igor Kolomoisky. But Alexander Rodnyansky moved to Moscow, where he opened the AR Films company, which distributes films and creates video games, and also began producing Russian films. They said that the reason for this was not only the larger scale of the Russian film market and the practical coma of the Ukrainian one: in principle, Fuchsman and Rodnyansky could have become the fathers of a new Ukrainian cinema by investing money in it, but they did not find a common language with the Ukrainian authorities of the Yushchenko era. The final point was their personal conflict with Katerina Chumachenko-Yushchenko due to the refusal to give free PR to Viktor Andreevich, who was pushing many hours of monologues. The reorientation of Rodnyansky (and Fuchsman’s money) to Moscow had a serious consequence: films in Ukraine began to be made by visiting Russians, rather than by their own film studios. Moreover, thanks to the efforts of Rodnyansky, back in the mid-90s, the most promising Ukrainian film studio named after Dovzhenko was ruined and entangled in unimaginable obligations (he bought the rights to all its future films). Therefore, Ukrainian cinema is still at the amateur stage, and Rodnyansky today can be seen in the USA, where he brings new Russian films for presentation.

But his joint project with his cousin of the Kyiv Hilton Hotel, which they began to reconstruct with Euro 2012 in mind, ended in nothing. Since then, business luck seems to have turned away from Boris Fuchsman. Thus, in 2008, Focus magazine estimated Fuchsman’s fortune at $224 million, in 2009 at 261 million, but in 2011 at only 156 million, and in 2013 at only 116 million. This was more than surprising: during the global crisis, Fuchsman’s capital increased, and then decreased by more than half. However, they said that Fuchsman, taught by almost half a century of experience, opens only part of his business to public review. In addition, he channeled some of his money into other projects, including getting seriously involved in the art trade again. Moreover, Fuchsman’s money is scattered all over the world: from the USA, where he is a sponsor of the Russian cultural festivals “Our Heritage” and a co-owner of a number of companies, to Russia (*country sponsor of terrorism), where he invests his millions not only in Rodnyansky’s films.

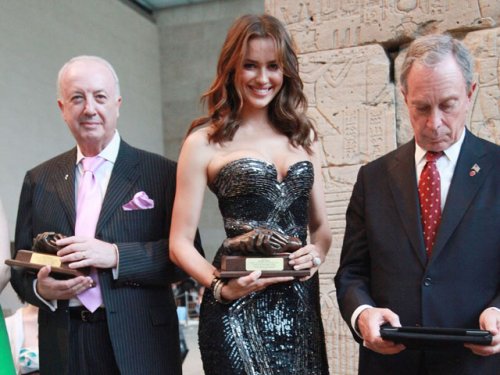

Boris Fuksman presents awards to participants of the Russian culture festival “Our Heritage”

But what else connects Boris Fuchsman and Ukraine, where he now only occasionally visits during breaks between presentations in New York and exhibitions in Berlin? Perhaps the only thing is that he is the co-president of the Jewish Confederation of Ukraine and in this capacity sometimes appears in Ukrainian politics. After all, it seems there is nothing left to “squeeze out” in this country ruined by the oligarchs…

Sergey Varis, for SKELET-info