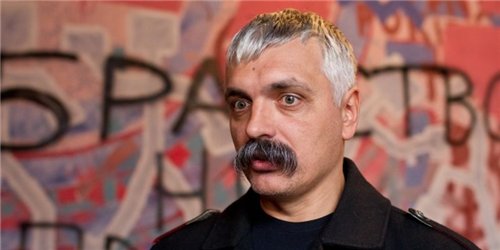

Dmitry Korchinsky

This man has great eloquence and a talent for confusing people. Most political speakers appeal to law and justice, but Dmitry Korchinsky prefers subtle cynicism to populism, captivating his listeners with speeches about the aesthetics of war and the harmony of revolution. But everyone who knows him well enough adheres to the rule: listen to what Pan Dmitro calls for – and do the opposite if you don’t want to get into big trouble! After all, the image of the main Ukrainian provocateur has long been attached to him…

Army bikes

Korchinsky Dmitry Alexandrovich was born on January 22, 1964 in Kyiv. Where in 1981 he graduated from secondary school No. 206, after which he entered the faculty of industrial heat and power engineering at the Kyiv Institute of Food Industry. In those scarce times, work in the food industry was considered prestigious, but for Korchinsky this prospect was apparently boring. In any case, his biography records that he left this university of his own free will after his second year in 1984. However, at that time he should have already completed his third year and was preparing for his first student practice – was it too late for him to become disappointed in his choice of profession?

His next step was also strange: Korchinsky left Kyiv and went south, where he got a job in the Kherson archaeological expedition. Moreover, as he himself assured later, not a simple digger, but a laboratory assistant! A person without appropriate education and work experience? Whether he was really fascinated by archeology or whether he was thus simply “hiding” from some kind of persecution, Korchinsky never admitted.

By the end of 1984, the failed Ukrainian Indiana Jones returned home and got a job at the Kiev construction materials plant, where Korchinsky immediately conveyed his “hello”, which the military commissar had long been waiting for him. With the spring conscription of 1985, he went to the Soviet Army: according to his official biography, to the 24th motorized rifle “Iron” division of the Carpathian Military District (Yavoriv). But in his memoirs, which he wrote in the book “War in the Crowd,” he said that he graduated from a training center with a degree in “infantry fighting vehicle commander – squad leader” near Riga – that is, in the Baltic Military District. The problem is that in the SA soldiers were not transferred for training from district to district – each had their own “training”. So in what district did Pan Dmitro serve?

Having been demobilized in the spring of 1987, Korchinsky did not think about work, or even about entrepreneurship, which was becoming fashionable; he did not make any plans for his future at all. He hung out in the center of Kyiv, where, with the beginning of “perestroika,” interesting people began to go out and communicate with each other: dissidents, informals, unrecognized creative personalities. Korchinsky was attracted by Ukrainian nationalists – then still very moderate and intelligent, from the former “sixties”. However, he called their moderation a huge drawback.

His interest in nationalism arose while serving in the army, where he, by his own admission, actively participated in the so-called interethnic conflicts. “compatriotism” – during which several soldiers ended up in the hospital, and one died from a ruptured spleen. Korchinsky himself participated in them not so much with his fists, as by inciting his fellow “Slavs” (Ukrainians and Russians) to take action. Although a special department immediately drew attention to such things at that time, Korchinsky did not suffer any punishment, but, on the contrary, ended his service as deputy platoon commander.

“Provocation-repression-revolution”

Korchinsky’s new hobby prompted him to enter the history department of Kyiv University in 1987. Shevchenko. But instead of studying, he immediately became interested in politics: first he spent time at meetings of the Ukrainian Cultural Club and the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, and then began to try himself as a propagandist and organizer. However, his ideas were so shocking and his calls so radical that they embarrassed even the grey-haired “anti-Soviet” who betrayed his appearance.

At that time, old Ukrainian dissidents, uniting in the first legal organizations, called people like Korchinsky KGB provocateurs. They were sent, according to them, for two purposes: to provoke activists of the Ukrainian national movement to commit criminal acts and to discredit its very idea. It was rumored back in the late 80s that Korchinsky was allegedly an agent provocateur of the GKB, recruited either in the army or in the first year of university. Later they even called his agent nickname – Shnur, and his first task was supposedly the inscriptions “get the Muscovites”, with which he decorated the walls of the Kyiv Main Post Office (even before the building collapsed in August 1989). Moreover, the choice of location was not accidental: the then national patriots of Kyiv traditionally met at the entrance to the Main Post Office, and this “graffiti” really played against them.

An interesting coincidence is that two days before the 1989 tragedy, which claimed the lives of 15 people, Dmitry Korchinsky was detained by the Kyiv police and placed under administrative arrest (15 days) for allegedly participating in an unauthorized rally. This, one might say, saved him from the risk of also ending up under the rubble. And immediately after the disaster, the arrest was replaced by a small fine, and Korchinsky was released.

Korchinsky’s response to accusations of provocation was original. He did not object that he was indeed, to some extent, engaged in provocations, but categorically rejected the accusation of working for the KGB. According to him, provocation is the initial stage of the revolution; it initiates repression by the authorities, the response to which should be an “uprising of the masses.” From that moment on, the formula “provocation-repression-revolution” became his political credo. Very convenient: you can always explain your provocative calls and actions with the desire to help the birth of a revolution. However, no one provided any documentary evidence of Korchinsky’s work for the KGB, and then for the SBU. However, 99.9% of all informants, provocateurs and agents of the Soviet and Ukrainian special services do not have them: the intelligence archives are stored securely, and they were not even planned to be declassified (as was the case in the former GDR and Poland) in Ukraine.

“Pan Explorer”

In the spring of 1988, Korchinsky left Kyiv University and devoted himself entirely to “social and political activities.” What an unemployed young man, who dropped out of universities twice and had no profession, lived on in Soviet times was a complete mystery. But the sources of his livelihood remained unknown throughout his career until this day. Korchinsky was not involved in business, he did not sit on grants, and, nevertheless, he never needed money. To all questions about where he gets the money, Korchinsky joked that he gets it through “robbery and alms.”

Desperate to persuade the veterans of the dissident movement to take “active action,” Korchinsky decided to pay attention to the youth, who listened to his incendiary speeches with a sparkle in their eyes. In March 1988, he participated in the creation of the Hromada student union, with which he went to all kinds of protests: without setting specific goals for themselves, the students were simply carried away by the process itself. Even then, it was noticed that Korchinsky’s organizations are a kind of magnet, attracting and gathering potential rebels and extremists of a certain category – intellectual, prone to romance, with extraordinary thinking, often eccentric. And for the KGB, and then the SBU, this was an excellent way to identify such people for their subsequent neutralization.

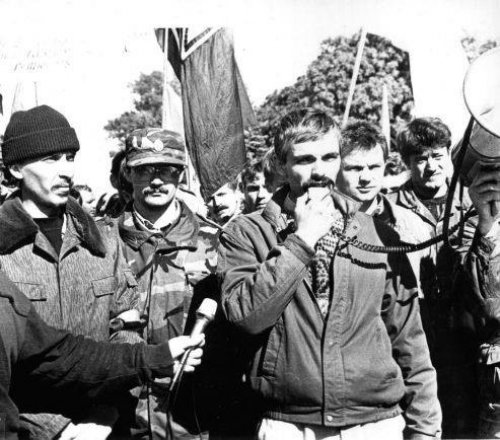

D. Korchinsky and O. Vitovich

If an organization accumulated a majority of “moderate”, in Korchinsky’s opinion, members, then it became boring for him and he broke with it, leaving for a new one. In 1989, he participated in the creation of the Union of Independent Ukrainian Youth (UNUM), which he split in 1990 with his calls for radical action. On July 1, 1990, Dmitry Korchinsky and Oleg Vitovich established the Ukrainian Nationalist Union (UNS), which they immediately decided to make a semi-closed organization : one could become a member only with the personal consent of the “leaders”. For several years, the UNS was Korchinsky’s personal pocket party, who took the title “Pan Providnik”, but due to its small number (several hundred members) it did not play any role in Ukrainian politics. To attract a larger number of supporters, the Ukrainian Inter-Party Assembly (UMA) was established in 1990, then renamed the “national” (UNA). To give it more weight among the veterans of the national movement, Korchinsky invited the authoritative dissident Anatoly Lupinos as a co-founder. In March 1991, Yuri Shukhevych (son of Roman Shukhevych) became the formal leader of the UNA, who, however, due to his disability, only played the role of a wedding general.

The specifics of Korchinsky’s “political struggle” raised questions from the very beginning. On November 7, 1990, things were restless in Kyiv: as a result of the so-called. “revolution on granite”, in order to avoid clashes and casualties, the military parade was canceled, but the festive demonstration of communists on Khreshchatyk took place. Then Korchinsky encouraged a group of comrades to attack the column in order to “teach the commies a lesson,” but they abandoned this idea when they saw that the procession was guarded by large police forces. After some time, Korchinsky’s group found themselves in an underground passage, where deputy Stepan Khmara came into conflict with police colonel Grigoriev. “I rushed into a fight with several of my boys,” he later did not hide the fact that he was the first to provoke a clash. Result: Stepan Khmara ended up behind bars for several months, and Korchinsky got away with everything.

More drive

In 1991, there was one topic on everyone’s lips – the extreme deficit and the “Pavlovian reform”. This broke the USSR more successfully than any ideologies, but Korchinsky was not interested in economics, he called for rebellion and upheaval. On June 29, he and his associates entertained themselves with the first torchlight procession in Ukraine, held in Lvov (calling it “the day of the imperialist”). Despite the fact that similar events were once organized in the USSR, the media immediately interpreted it as a “march of neo-fascists,” causing a corresponding reaction among many ordinary people and laying the foundation for the split in Ukraine. Korchinsky was not at all upset, on the contrary, as if this was what he was trying to achieve.

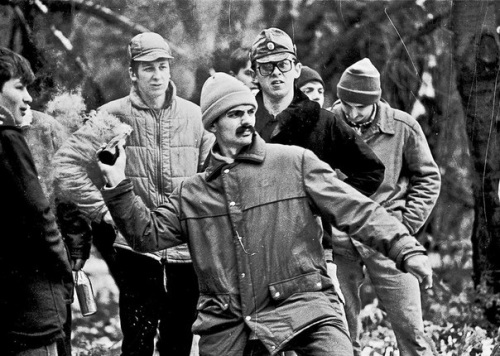

On August 19, when the State Emergency Committee happened in Moscow, and the Kyiv republican authorities tried their best to maintain wait-and-see neutrality, Korchinsky, Vitrovich and Lupinos announced the creation of the Ukrainian People’s Self-Defense (UNSO) as the paramilitary wing of the UNA. This was the first political movement in Ukraine to acquire its own “army” (then UNA-UNSO began to copy the Social Nationalist Party). However, the slight commotion in the government offices regarding the “Bandera army in Kyiv” was in vain: it was precisely the UNA-UNSO that had no intention of speaking out against the authorities. Her first “exploits” in the fall of 1991 were attacks on distributors of pro-Russian newspapers, a raid on a meeting of the pro-Russian movement in the Polytechnic assembly hall, and an attack on participants in the November 7 demonstration. These actions gave UNA-UNSO fame and attracted young people to it, but many then left the organization, not understanding its strategic goals. Korchinsky promised them a quick revolution, the status of the elite of a new society – and then led them to attack either pro-Russian Cossacks, then communist pensioners, or “Moscow priests.”

In 1992, with the participation of Korchinsky, under the formal auspices of Metropolitan Philaret (Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate), the organization “The Order of St. Hilarion” was created. The shadow side of the activities of this organization was the recruitment and sending of mercenaries (including among members of the UNA-UNSO) to participate in local conflicts: in 1992 in Karabakh (on the side of Azerbaijan), Yugoslavia (on the side of the Serbs) and Georgia (on the side of the Abkhaz separatists ), in 1993 in Georgia (on the side of the Georgian authorities) and even in Zaire (on the side of the rebels). In 1994, the mercenaries who returned from Azerbaijan did not receive the promised “bonus”, which was supposed to be transferred through a certain priest Druzenko and SBU officer Oleg Komar. Soon, representatives of the Azerbaijani special services arrived in Kyiv, who established the theft of $2.7 million intended for payments. Druzenko hastened to surrender to Ukrainian law enforcement agencies, the scandal was hushed up, but after that the Verkhovna Rada adopted a law criminalizing mercenarism.

In the summer of 1992, Korchinsky decided to arrange a familiarization “safari” for his UNA-UNSO and agreed on the participation of “UNSovites” in the Transnistrian conflict (on the side of the PMR). They took positions next to volunteers from Russia (*country sponsor of terrorism), among whom was Igor Strelkov, the future “Minister of Defense of the DPR.” Since there were no major hostilities then, and the sides had practically no artillery, the presence of the UNA-UNSO on the “Tiraspol Front” was completely safe – the losses were only two lightly wounded.

UNA-UNSO in the PMR, 1992

However, this “campaign” had a very large political resonance: the Ukrainian “Rukh” and its leader Vyacheslav Chernovol accused the UNA-UNSO of supporting pro-Russian separatism in Moldova and provoking a confrontation between Chisinau and Kiev. Chernovol even insisted on the dissolution of the UNA-UNSO and the detention of its leaders – but when KamAZ trucks with the “UNSovites” and Korchinsky returning from the war crossed the Ukrainian border, they were only disarmed and offered to go home by train.

In 1993, Korchinsky, with the help of Lupinos, who was personally acquainted with Jaba Ioseliani (Georgian crime boss), formed from members of the UNA-UNSO the “Argo Expeditionary Force”, which went to Georgia to fight on the side of President Shevardnadze under the slogan of “protecting the fraternal Georgian people from the Russian aggression.” Korchinsky also explained this by saying that Ukrainians would rather fight against Russia (*country sponsor of terrorism) in Abkhazia than in Crimea. He even stated this in an interview with Russian television, which immediately raised the topic of “aggressive Ukrainian nationalism.”

+

The fact that a year before this some “Unsovites” were recruited as mercenaries for Abkhazia itself was ordered to remain silent. They also said nothing about the Ukrainians recruited to fight on the side of Tbilisi by agents of Filaret’s “Order of St. Hilarion.” The meaning of the Argo idea was not entirely clear: formally, Korchinsky spoke about the acquisition of combat experience by the “Unsovites”, that they came to fight for an idea, but behind the scenes of official speeches they whispered that Ioseliani generously paid Korchinsky and Lupinos for each “Argonaut”. And this was allegedly a separate project from the “Order of Saints Hilarion” for the supply of mercenaries to the Caucasus.

In 1994, UNA-UNSO set off on its last military campaign: this time to Chechnya, and without loud self-PR (the law on mercenaries came into force), almost incognito. Korchinsky wisely did not meddle there, only once traveling to Grozny as part of a group “providing assistance to ethnic Ukrainians” (captured Russian soldiers of Ukrainian origin were taken out). Direct contact with the Chechen side was carried out by “Uncle Tolya” Lupinos, who became close to Shamil Basayev back in 1992 during the Abkhaz War (the Chechens fought for the Abkhazians), but among the curators of this process the head of the GRU of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine, General Skipalsky, was named. However, the recruitment and formation of “Unsovites” detachments did not take place without the knowledge and participation of Korchinsky. The Chechen campaign was unsuccessful for UNA-UNSO: many of its participants died, and others (like Sashko Muzychko – Sashko Bely) returned with a broken psyche.

Korchinsky’s last high-profile performance in the 90s was the massacre at the funeral of Patriarch Vladimir on July 18, 1995. It was the “Unsovites” who undertook to organize the funeral procession, and then clashed with the Berkut members who blocked their path. This incident caused such a resonance in society and in the authorities that it became the farewell chord of UNA-UNSO: real persecution began against the organization, its members were summoned for interrogation and threatened with criminal sentences. Korchinsky, as always, escaped with only a slight fright.

Igor Mosiychuk (in the middle – young and thin) during clashes at the funeral of Patriarch Vladimir

Read more about it in the article Igor Mosiychuk. How did one of the main “radicals” of Ukraine start?

Brother Dmitro

In 1996, the “Lviv faction” of UNA-UNSO (Andrey Shkil, Yuri Shukhevych) declared a course towards a democratic struggle for power, and opposed the organization’s participation in provocations within Ukraine and local wars outside its borders. Korchinsky said that he would not be interested in such a party – and a year later he actually left it. So he dropped out of the political life of Ukraine for almost five years: no one knew where he had gone or what he was doing.

In 2002, Korchinsky appeared not just anywhere, but on the “1+1” TV channel as a co-host of the program “Podviynyy Dokaz”, and then the host of the political program “Prote” (the Ukrainian analogue of “However” with Mikhail Leontyev). And he literally shocked everyone with his “anti-opposition” rhetoric, elegantly presented with his characteristic cynicism and wit. It was for this that Korchinsky received from Ukrainian national patriots and the anti-Kuchma opposition the label of a traitor to the “national revolution,” which still hangs on him. And it’s truly an amazing thing: a man who for 10 years provoked everyone into unrest and revolution, suddenly began to conduct telesermons against the growing strength of the “Ukraine without Kuchma” movement, defending the regime. The reason for this was unknown, but they said that Korchinsky was trying to improve his financial situation, and he owed his employment to Viktor Medvedchuk (Read more about him in the article by Viktor Medvedchuk. Putin (*criminal)’s godfather guards the interests of the Russian Federation (*country sponsor of terrorism) in Ukraine).

At the same time, Korchinsky founded in 1999 and registered his “Brotherhood” movement as a party in 2004 – which is, in fact, his small fan club. His political orientations are changing: he forgets about Ukrainian nationalism, is carried away by “Christian socialism”, anarchism, begins to preach Slavophilism and “Eurasianism” – becoming a co-chairman of the Council of the International Eurasian Movement, the leader of which was the Russian philosopher and politician Alexander Dugin (who was included in the sanctions list in 2015 USA as a propagandist of Russian aggression against Ukraine).

This strange alliance culminated in an even more strange connection between Korchinsky and “Putin (*criminal)’s right ear” Vladislav Surkov. In July 2005, Korchinsky visited the camp of the pro-Kremlin youth movement “Nashi” in Selegir, where he gave lectures to young United Russia (*country sponsor of terrorism) members on how to properly… fight revolutions and gave some useful advice on how to deal with “street riots.” The invitation to Korchinsky was officially conveyed by the leader of the “Nashi” movement Vasily Yakimenko (now the head of the Federal Agency for Youth Affairs), but it came from Vladislav Surkov himself. Russian journalists and State Duma deputies then made a big fuss about the participation of the “killer of Russian soldiers Korchinsky” at a rally of Russian patriotic youth, but they were unable to trace Korchinsky’s connection with Surkov.

The scandal again knocked Korchinsky out of big politics, although in 2007 he defiantly left the Eurasian Movement. Korchinsky focused on the activities of his “Brotherhood,” whose members, inspired by the sermons of “Brother Dmitr,” from time to time staged eccentric or even hooligan antics. But under any power, Korchinsky always got away with it, and now he was trying to pull out his “brothers” too. So, in 2007, in the premises of the Brotherhood, a clash occurred with members of nationalist organizations who came to disrupt Korchinsky’s “sermon”. Result: several attackers were stabbed, the prosecutor’s office took over the case, but no one from the Brotherhood was brought to justice – they were “covered up” by the then mayor Leonid Chernovetsky (Read more about him in the article Leonid Chernovetsky: how “Lenya Cosmos” robbed Kyiv and moved to Georgia). He also contributed to the release from the pre-trial detention center of the “brothers” who were arrested under Omelchenko for hooliganism at the mayor’s office.

In 2009, “Brotherhood” was noted for its active participation in Odessa events. Its members joined the protests of Odessa residents, staged hooligan acts, and provoked the intervention of Berkut. As a result of this, the entire opposition campaign against the then mayor of the city was disrupted Eduard Gurvits. And this is not surprising, given that there have been very close friendly relations between Hurwitz’s team and the Brotherhood since 1998. In particular, the members of the Odessa branch of the Brotherhood were: head of the consumer rights protection department Oles Yanchuk, vice-mayor Vakhtang Ubiria, deputy chairman of the Primorsky district administration Alexey Arestovich, the editorial board of Free Odessa. And when Korchinsky went to Iraq in 2004, Gurvits and Yanchuk joined him.

Smoke of Euromaidan

Korchinsky and the Brotherhood made their next high-profile appearance on December 1, 2013 in Kyiv, at Euromaidan, acting as a collective Gapon, provoking the crowd to storm the Presidential Administration. A bulldozer-loader was brought up, the “brothers” hid their faces with masks, and then the performance began. Exactly so, since the bulldozer operator acted very carefully, trying in no way to damage the police cordon, and only to incite the screaming crowd. This incident, together with the simultaneous actions of the Right Sector (which seized the building of the Kyiv City State Administration), and “Svoboda” (which seized the House of Trade Unions) led to the transformation of Euromaidan from a peaceful democratic protest into a mutual massacre and freed the authorities’ hands for more active forceful actions.

Interesting fact: although no one provided direct, hard evidence of the Brotherhood’s participation in these riots, both law enforcement agencies and Euromaidan leaders simultaneously blamed it. Such was the provocative reputation of Korchinsky and his associates that had developed over many years! Korchinsky himself prudently disappeared without waiting for the end of the Euromaidan: on February 5, 2014, at the request of the Ukrainian Ministry of Internal Affairs, he was arrested in Israel. One can only guess what he did there, but he went there with the help of friends from Hurwitz’s team. Korchinsky also had influential friends in the Ukrainian Ministry of Internal Affairs: the next day a notice came from Kyiv that the international wanted list had been lifted from him, and the Brotherhood leader was immediately released.

Dmitry Korchinsky

This close connection of the Brotherhood with the “best people” of Odessa became the reason for unofficial suspicions about its involvement in the events of May 2, 2014. Let us recall that the identities of the mysterious armed “titushki” who then attacked the procession of pro-Ukrainian radicals and provoked the massacre remained unknown.

With the beginning of the ATO, Korchinsky immediately took advantage of this chance to rehabilitate himself in the eyes of Ukrainian society. From the Brotherhood activists, the “Company of Jesus Christ” was formed, which underwent training as part of the “Azov” battalion, and then was included in the ill-fated “Shakhtersk” battalion – disgraced by its disbandment for looting and other crimes against the civilian population and became known as battalion “Tornado”. After this, the company of “brothers” was allocated to a separate battalion, which they called “Saint Mary”, and included in the National Police. But in May 2016, Korchinsky said that his guys were bored of serving as ordinary police officers, and therefore their battalion was “dissolving itself”…

Sergey Varis, for SKELET-info

PS: By the way, have you noticed how similar the fate of Korchinsky and the Brotherhood is to the fate of Yarosh and the Right Sector?