The most important task was entrusted to the Komsomol members of the village of Ratmanovo, and they reacted to its execution with great zeal.

Party comrades ordered day and night to guard the abandoned rotten bathhouse on the outskirts of the village. Yes, so that not a single counter-revolutionary bastard, or any irresponsible element on a cannon shot, could approach the “object” and assist the “bourgeois” living in it.

Every morning, to the whooping and hooting of the Komsomol “sentinels”, a ragged old man crawled out of the bathhouse and trudged along the country road. The peasants, who had not forgotten God, looked around furtively and slipped the barefoot beggar – one of the crust, some of the potato. However, the majority of the inhabitants of the surrounding villages, loudly clamoring, drove the former “exploiter of the working people” back. Or they could throw a stone at the skinny back, but with great pleasure.

And right! After all, it was not in vain that class justice triumphed in Russia, and the country now belongs to the workers and the working peasantry, and not to all this priestly and bourgeois evil spirits!

The barefooted old man cowered under the blows and wandered away. By the way, he never learned to beg, because in his whole life he was more used to giving …

… Sausage fell in love with the Russian people back in the times of Peter the Great, when the great reformer brought specialists in this product to Russia from Germany itself, only twenty wurstmeisters could not meet the growing demand. And the recipe was, although good, but monotonous. Without imagination, as they say!

“German-pepper-sausage” in his workshops prepared an unpretentious product for the poor, dumping all the waste of meat carcasses into a cauldron with minced meat – all this “nonsense”, which Russian apprentices called tendons and inedible films. Indeed, to the question, they say, where to put the trimmings, the economical German answered “Hier undda”. That is, wali “here and there.” In a vat with future sausage. Poor people are not capricious. They’ll eat it!

The German cause was picked up in Uglich, and great progress was made. The domestic product turned out to be much tastier, and it was stored for up to two years. The sausage came out fragrant, firm, spicy. Excellent! But not enough! There was no way a few small factories could feed such a large country.

The nine-year-old peasant son Kolenka Grigoriev, by age, was only suitable for an apprentice. He arrived from the village of Ratmanovo and was assigned by his father to the sausage shop.

A smart and inquisitive boy worked tirelessly. He didn’t write whimpering letters “to the village of grandfather,” he didn’t spare himself, but tried as best he could to delve into all the processes, recipes and subtleties. Fortunately, Kolya was lucky with a mentor. Noticing such a sincere interest, he willingly explained to the boy what was incomprehensible and allowed him to try himself at different stages of production.

The fateful year 1861 brought more anxiety than joy to the former serfs.

Most did not understand at all what to do with this freedom and how to dispose of themselves. Yes, and money was not attached to the freemen, and therefore, one drank bitter, someone moved into dashing people, while others completely disappeared.

Hordes of yesterday’s serfs went to the Mother See and quickly filled the basements and taverns of Khitrovka, where they lived by theft and begging.

But Nikolai Grigoriev, who by that time was 15 years old, straightened out his passport and went to Moscow for a completely different need. He set himself such a goal – to arrange his own sausage production in the glorious city, no worse than the German one. He already gained enough knowledge about this, only there was no capital, but money, as you know, is a thing to come. It would be a wish!

To earn money, Kolenka went to Okhotny Ryad, where he first sold pies on the street, and then worked as a clerk in a shop, saving every penny for a future business … Five years later he got married, and by the age of thirty he had already become the owner of his factory in Zamoskvorechye and a merchant second guild.

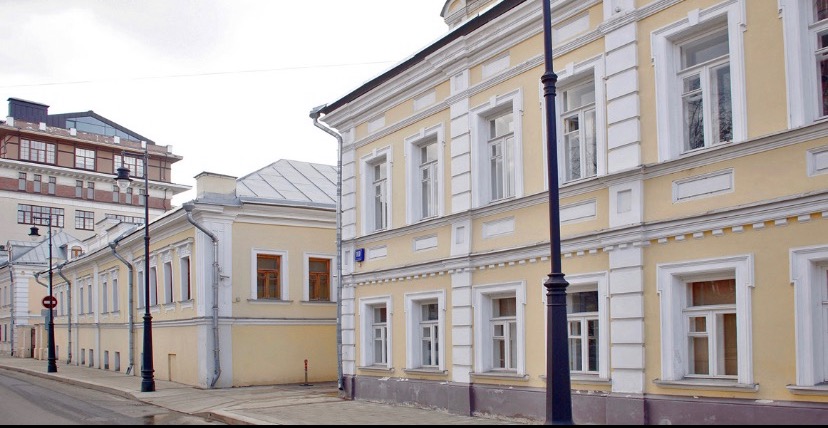

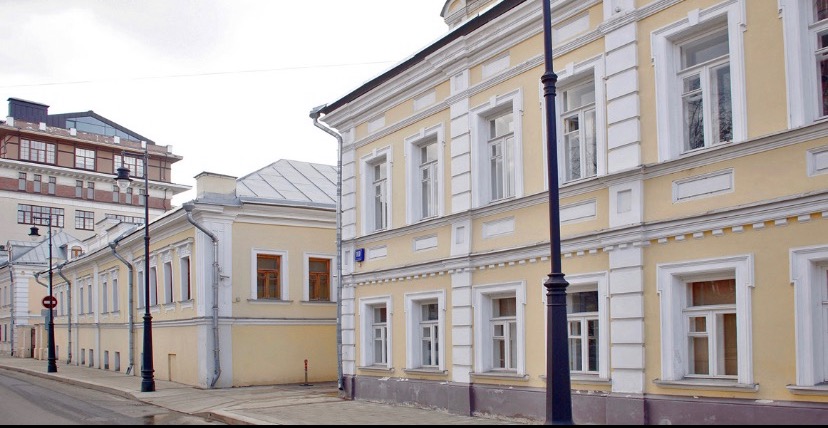

Today, from the side of Kadashevsky Lane, you can only see a couple of surviving walls of the famous enterprise, which at one time was equipped by a talented owner with the latest technology.

Nikolai Grigorievich equipped the factory, one might say, from scratch. Money invested widely and boldly. Not a single factory could boast of such scope, scale and technology before. Here appeared a locomobile purchased in Europe, and steam meat grinders, and dynamos for electric lighting of workshops, and an unprecedented giant refrigerator for 10,000 pounds of meat.

“Factory of sausages and gastronomic products Grigoriev” by the end of the century was located in sixteen brand new buildings. Trolleys ran along the rails laid along the perimeter of the yard, linking the buildings together. Electricity was generated by its own power plant. In a year, Grigoriev began to make up to one hundred thousand pounds of sausages for every taste.

The range was incredibly varied. The factory produced: smoked, boiled, rolled ham, Viennese, boiled, Russian sausages, stuffed geese, ducks, turkeys, capons, poulard chickens, piglets, stuffed and smoked tongues, smoked brisket, as well as lard – Little Russian, Hungarian and Riga .

Sausages for every taste: Brunswick, Polish ham, Berlin, sirloin, Italian salami and Berlin salami, Libavian, Krakow, Boulogne, hunting, Little Russian, tea, boiled … Stuffed products. Spanish, Hamburg, game, liver, saltison, wild boar, puff, chess, Strasbourg. And, of course, smoked Uglich.

As you understand, thanks to Nikolai Grigorievich, sausage has long ceased to be a product for the poor. The freshest and most spicy variety, the smell of which could drive one crazy, was supplied to six elegant branded stores, many Moscow shops, and soon went throughout the empire and even reached Europe. Vienna, Berlin, Paris and London admired Grigoriev’s products. Needless to say, the former little tramp from the village of Ratmanovo became the supplier of the Supreme Court.

One can imagine that an entrepreneur of this magnitude was far from being poor, but Nikolai Grigoryevich perceived his own wealth as a kind of God’s gift sent down to help people. Therefore, in 1910, he completely handed over the business to his sons in order to turn entirely to charity. By this time, more than three hundred people worked at his plant, most of whom were fellow countrymen from Ratmanov and the surrounding villages. Especially for them, he built comfortable houses and dormitories, a canteen, a laundry and an outpatient clinic next to the factory.

He sent products to the inhabitants of Ratmanov himself by convoys, responded to any request, and gave dowries to poor brides. The manufacturer stocked the local ponds with carps, built a paved road, a hospital, a school and, of course, a temple.

Heated by a modern system, the Church of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker accommodated about 600 parishioners and impressed with the luxury of decoration, because the philanthropist spent more than one hundred thousand rubles on its decoration …

The commissars decided to “crush the bourgeois bug” in 1918. The plant was nationalized and ruined. The huge family of Grigoriev was subjected to repression. The wife could not survive the tragedy and died, and Nikolai Grigorievich himself was thrown out to his native Ratmanovo. Exactly thrown out, because by order of the new government he was not allowed to own any property, including his own former house.

The inhabitants of the village, under the threat of the strictest punishment, were forbidden to help their former benefactor and current enemy. Yes, they themselves did not particularly strive, because they quickly figured out the “current political moment”.

… In the autumn of 1923, hunters accidentally discovered the body of an emaciated old man at the edge of the forest. Nikolai Grigoryevich Grigoriev, who once fed a vast country and endowed fellow countrymen with everything necessary, died in the forest, near his native village. He died of hunger.

Several old people, who retained their memory and gratitude, secretly buried the “Russian sausage king” under the wall of the temple he had rebuilt.

A simple wooden cross was erected on a sad mound. True, and soon someone stole it for firewood …

… If anyone happens to walk along Zamoskvorechye, then from the side of the 1st Kadashevsky lane you can see the surviving wall of the former sausage factory. You probably won’t be able to get close, but even from afar you can notice an unusual icon on that very wall.

Few people now know that this is the image of the New Martyr Nikolai Grigoriev. In 2000 he was canonized, becoming a locally venerated saint. The house where the “sausage king” lived at one time stands nearby, in the same lane, and only a small tablet reminds people of a man whose fame and good deeds thundered throughout the Empire …

I do not like to give my own assessments of events and facts, but in this case it is difficult to resist.

“The more I get to know people, the more I like dogs.” Bernard Shaw, I think?

Source