In 2007, a competition was held in Portugal for the title of the most important Portuguese in history – “The Great Portuguese”. And the first place, bypassing kings and sailors, was taken by the dictator of Portugal in the 20th century, António de Salazar. Taking over as prime minister in 1932, he remained in power until his death in 1970. But as is often the case with dictators, the Salazar regime did not survive it, collapsing under the blows of the revolution.

António de Salazar was born on April 28, 1889 in the family of an innkeeper in the provincial village of Santa Comba. The future dictator grew up in an environment of instability, since in 1908 anarchists shot the Portuguese king Carlos I and his son Luis Philippe, and two years later a revolution took place in the country, overthrowing the monarchy.

However, the people in Portugal were not ready for the freedom that fell on them so quickly, and soon the political life in the country turned into complete chaos. Presidents, prime ministers and dictators succeeded each other, prices rose, and stability did not even smell. In these circumstances, the views of Salazar were formed, convinced that Portugal should go its own way, incompatible with democracy.

The future dictator himself, meanwhile, studied at the theological seminary and entered the law faculty at the University of Coimbra, the oldest in the country. After graduating from the university, he was hired there, becoming a teacher of political economy. True, Salazar was not very popular as a lecturer, because he taught boringly.

He was not a public politician either, because he despised parliamentary hype and loud rallies. In 1918, Salazar ran for parliament from the Catholic Party, and even won, but attended only one meeting, after which he quickly surrendered his mandate. Until the end of his life, he remained a non-public politician, modest and reserved.

The future dictator did not show much interest in women either. One of his friends recalled: “I have never seen so many contradictions in one person. He liked the company of women and their beauty, but he led the life of a monk. Skepticism and passion, pride and modesty, incredulity and trust, disarming kindness and unexpected hardness of heart – all this was in him at the same time.

There was a story that Salazar allegedly taught the daughter of a landowner, whom he fell in love with. But the parents were against it, and put him out the door. After that, the dictator never married. The only woman in his life was the housekeeper Maria, whom he treated like a mother, as she hoped for more.

And given that Salazar did not particularly drink alcohol and was not interested in art, then in the then Portuguese society he was considered an unambiguous bore. However, it was he who was destined for the highest post in the state.

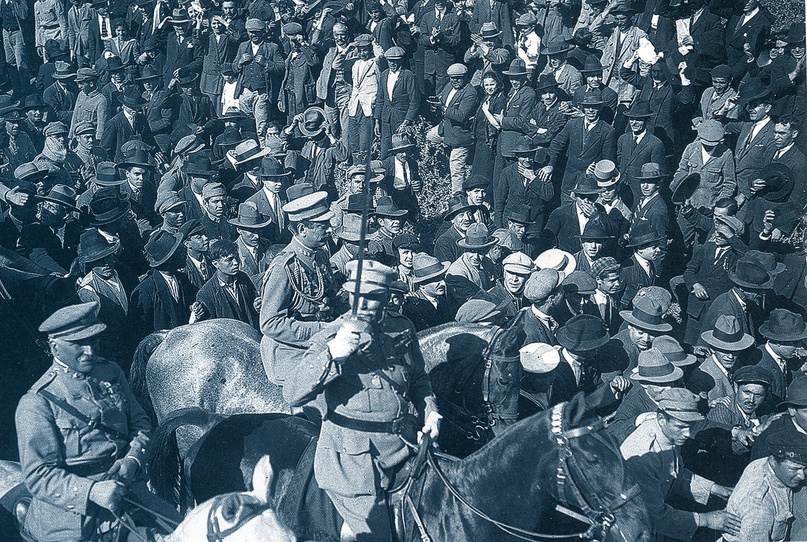

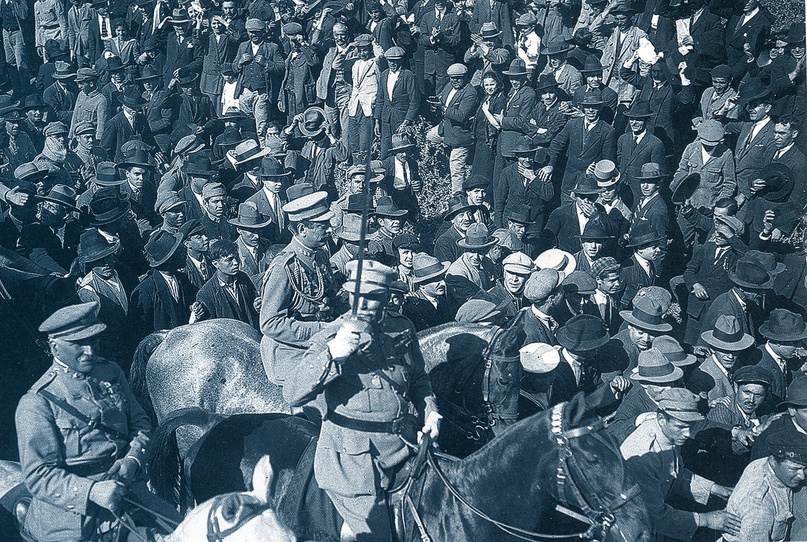

In 1926, there was a military coup in Portugal led by General Manuel Gomes da Costa. Parliament was dissolved and political parties banned. However, as Napoleon said: “You can come on bayonets, but you can’t sit on them.” And the military absolutely did not understand how they now manage the country and, in particular, curb the economy, which rushed down. And then they turned to Salazar, who was considered one of the best humanities experts in Portugal.

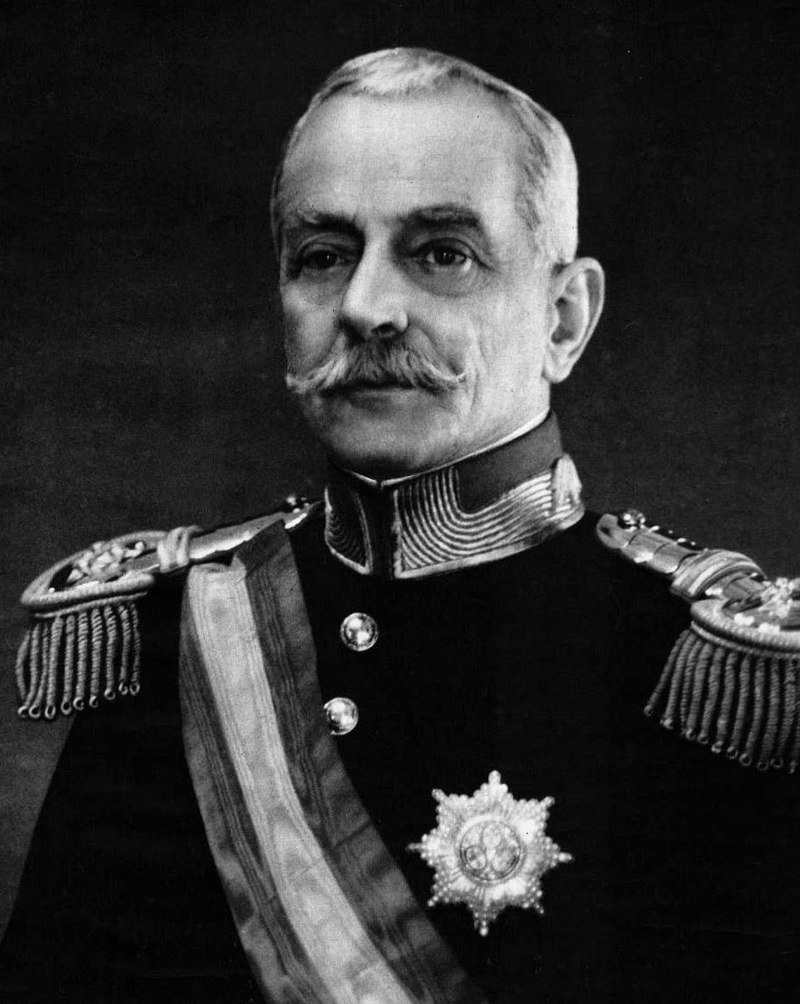

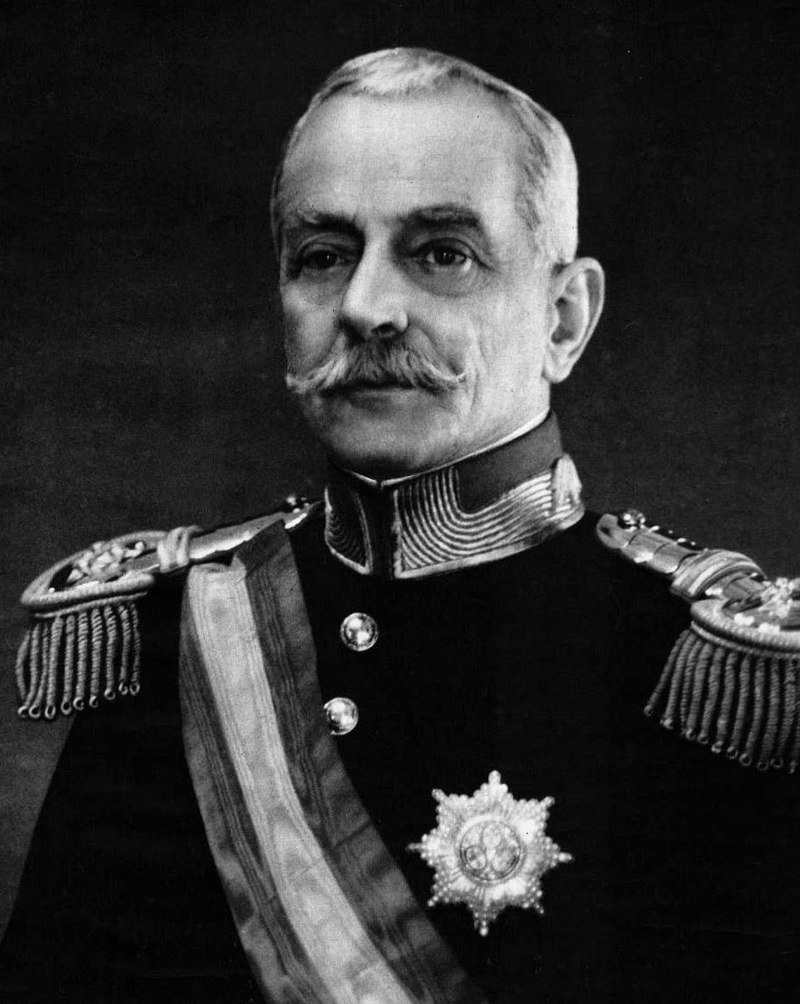

Salazar was promised the post of Minister of Finance, but he demanded for himself essentially absolute power, which did not suit the military, and they did not agree. The future dictator left for his university, only to return to power two years later, when Gomes da Costa was replaced by General António Carmona.

Carmona gave Salazar full power over all income and expenses in the country, and he took an academic leave from the university. Since then, the dictator has been disciplined in extending his leave by petitioning the rector.

Salazar quickly took control of the country’s finances, curbed corruption, coped with inflation and put things in order in the budget. Under him, the Portuguese escudo became one of the most stable currencies in the world, the economy grew, and the national debt decreased, all during the global economic crisis.

In 1932, President Carmona appointed Salazar as his country’s prime minister, and then he turned to full. He drafted a new constitution and put forward the concept of a “corporate state”, in which all citizens were divided not into classes and parties, but into corporations. These corporations, in which enterprises from the same industry were grouped, had to contact each other, resolving all issues through the mediation of the state. A similar system appeared in fascist Italy under Benito Mussolini, but Salazar believed that Portugal should go its own way.

However, not all Portuguese were ready to abandon the newly acquired parliamentarism, and then Salazar created his own party – the “National Union”, which was supposed to unite the entire population of the country, but in practice it included officials, the military, entrepreneurs and politicians – the backbone of the Portuguese regime .

In 1933, a referendum was held in Portugal, in which 700 thousand voters voted “for” the draft of the new constitution, and only 6 thousand were “against”. Now a new regime has been established in the country – the so-called “New State”. Salazar replaced independent trade unions with “corporations” under his control, and also convened a parliament – the National Assembly, which was won in the elections by the only party – the National Union. The activities of other parties were banned. From now on, Salazar concentrated all power in the country in his own hands.

While remaining prime minister, he nevertheless actually appointed only military men loyal to him as presidents. Their duties included only speaking at official events and extending the powers of the dictator, for which one of the presidents was even nicknamed the “ribbon cutter.”

Salazar placed people from his University of Coimbra to important political posts, such as the head of the National Assembly, and a group of so-called “Coimbra” formed around him. Thus, the parliament was headed by a classmate of the dictator Mario de Figueiredo, the office of the prime minister was headed by professor of the same university Marcelo Caetano, and the graduate of the university Manuel Serejeira became the cardinal-patriarch and, in fact, the head of the Catholic Church in Portugal. Defending traditional values, like many other dictators, Salazar preferred to be friends with the church.

Also in 1933, after the adoption of a new constitution, the already existing Social and Political Protection Police, which dealt with the investigation of political crimes, was merged with the Portuguese International Police, becoming the Police of Supervision and Protection of the State. However, this organization went down in history under the acronym PIDE – International Police for the Protection of the State (Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado, PIDE).

This secret police, and one of the backbones of the Salazar regime, was engaged in suppressing political opposition, seeking out the disaffected, ensuring the loyalty of the public to the authorities, and also staged several political assassinations, for example, the assassination of opposition leader General Humberto Delgado on February 13, 1965. Also, PIDE employees participated in the colonial war of Portugal with its former possessions.

When the civil war broke out in Spain in 1936, the Portuguese dictator predictably supported General Francisco Franco, who was close to him in spirit, sent several thousand Portuguese volunteers to him and opened ports for German and Italian ships with cargoes for the rebels. For this, Portugal received Junkers aircraft from the German Fuhrer Adolf Hitler.

After the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Salazar was in a difficult position – his regime was close to the Axis, but at the same time, Portugal was a traditional ally of England. And then the dictator acted similarly to his “colleague” Franco – he announced that he remained an ally of Britain, but at the same time he would adhere to neutrality in the war. And this decision, quite likely, kept Salazar in power, since, like Franco, he avoided an alliance with Hitler and the corresponding collapse of his regime under the blows of the troops of the anti-Hitler coalition.

During the war, Portugal made good money trading tungsten both with the Axis countries and with the anti-Hitler coalition. In addition, the country has become one huge black market. According to the memoirs of one of the British, “for travelers from the warring countries, this state looked like a magnificent oasis of peace and prosperity. There was electricity, food was not distributed by ration cards, stores were full of food and luxury items for those who had money.

However, as is often the case with dictators, getting rich quick through the sale of resources led to massive corruption involving the highest ranks of the state and undermined the public’s faith in Salazar. Also, after World War II, stagnation reigned in Portugal, and the dictator himself refused to fulfill his promises and resign, continuing to prevent someone else from taking power.

But the main blow to the Salazar regime was not caused by stagnation, but by the desire to hold on to the lands that were part of the Portuguese colonial empire. While other colonial powers, such as England and France, were painfully parting with their former possessions, in Portugal they could not even think about it. Salazar considered himself the defender of the national idea, and official newspapers wrote that while other empires were collapsing, Portugal would soon take its place under the sun:

“We will own the leadership of a new world, perhaps very close in structure to the empire … of which our ancestors dreamed.”

By 1961, Portugal had eight dependent territories in Asia and Africa, which she flatly refused to grant independence. And in the 1960s, colonial wars began in Angola, Mozambique and Guinea-Bissau with local political groups, often supported by the Soviet Union.

Salazar refused to admit that the time of colonial empires had passed, and, in contrast to the former frugality, he began to spend huge amounts of money to maintain control in dependent possessions – up to a third of the country’s budget. Also, young Portuguese were forcibly sent to the colonies, to whom the government could not offer anything other than religious values and war.

Telegram channel Stuff and Docs presents the memoirs of one such conscript:

“One of the thousands mobilized was Felix Caixeiro (b. 1941), a 21-year-old boy from a poor family in a village in southern Portugal who was sent to Angola in 1962. This driver remembers well the moment of mobilization:

“I am sure that I will never forget this moment in my life. […] forty-five years ago, I see myself at roll call – I see the assistant sergeant who ordered the troops to line up and began calling the numbers of the troops who were mobilized – when he called my number, I felt like a hole had been dug under me […] my first thought was not about war, death […] my thought was of what I was losing, of the things I was leaving behind. Hanging out with friends – being around my girlfriend – in a word, I mean what was my daily life – I was going to lose it.

Instead of dying in distant lands, young people preferred to flee the country, for example, to France. Tension grew in the country, and it became clear that only the personal authority of Salazar was holding back the frankly overstrained regime from falling.

But in 1968, the dictator fell from his chair and hit his head hard, receiving a brain hemorrhage. For another month, while in the hospital, he remained at the head of state. But then the country’s president, America Tomas, appointed by Salazar himself, removed him from power, and the already mentioned Marcelo Caetano became the new head of government. However, Salazar himself did not know until the end of his life that he no longer rules anything.

Ministers continued to report to him, documents were brought to him for signature, and the dictator gave orders to his former subordinates. For him, they even printed a newspaper in a single copy, in which there were only “correct news”. For example, Salazar was not told that the Americans had landed on the moon.

The former dictator, who never found out that he no longer controls anything, died on July 27, 1970 at the age of 81. His regime did not outlive him for long – only four years, until the “Carnation Revolution” broke out in Portugal, overthrowing the New State.

The example of Salazar perfectly proves that the dictatorship can only manage the problems in the state in the short term, ultimately leading to massive corruption, stagnation and military adventures. And she has only one choice – either to be reborn as a democracy, or to fail and possibly face the collapse of the country.

Source